“The feedback from the parents of the children attended by our students provided very positive information for evaluating the competence: professionalism.”

Childhood obesity is the cause of serious diseases such as diabetes, hypertension, heart failure, certain types of cancer, and depression, among others (Pérez-Herrera and Cruz-López, 2019). Mexico occupies one of the first places in childhood overweight and obesity problems (UNICEF, n.d.); therefore, it is necessary to raise awareness among future health professionals from the earliest stages of their training. However, presenting students with statistics and numbers foreign to them does not generate the necessary impact for developing the professional skills they need. But what if we brought them closer to their community for direct experience so that they assimilate the problem of child malnutrition in Mexico differently? Below, we share our experience.

The teachers participating in this project realized that generating awareness in our students about a problem is more enriching if the analyses and discussion of government reports and institutional organizations are integrated with their direct participation in producing some of the statistics reported in the literature in this project. This experience allowed students to generate more complete solution proposals based on their evidence and data reported by other entities.

“The most efficient way to make students aware of the magnitude of a real problem in the professional field is to discover it from within, knowing the individuals who make up the target population.”

Tec students investigate child malnutrition in their communities.

In Mexico, serious health problems have worsened in recent decades; particularly, overweight and childhood obesity predispose children to develop metabolic and cardiovascular diseases (Pérez-Herrera and Cruz-López, 2019). Therefore, we need to raise awareness among health sciences students (HS) about this problem early in their training.

For this reason, the teachers of the training unit (TU) “Life Cycle: Childhood and Adolescence,” which is offered in the second semester of the Health Sciences careers at the School of Medicine and Health Sciences (EMCS) of Tecnologico de Monterrey, considered the following question: What would be the results of assimilating the child malnutrition problem in Mexico by HS students who participate directly, reproducing some of the statistics reported in the literature, and, based on their evidence, generate a proposal for improvement?

To achieve this, we designed a five-week challenge. In the first stage, individual students collected information from one to five children to document their developmental status, eating habits, physical activity, oral hygiene, and other aspects of child well-being. The population is from a preschool sample in the municipalities of Cerralvo, Pesquería, Dr. Gonzalez, and Apodaca in Nuevo León, Mexico. In the second stage, based on the analysis of this information, the students formulated an improvement plan for the population studied and provided a basic health assessment directly to the child’s guardian, who, in turn, provided feedback on the student’s professional performance. The challenge was developed within the framework of the “Children’s Comprehensive Welfare Program (PIBI),” established with the support of the EMCS and the head of Zone No. 14 of the Ministry of Education of the State of Nuevo León.

It is worth mentioning that the first implementations of the training unit occurred in the February-June 2021 semester, practically one year after the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic in Mexico. Due to this situation, the approach to the challenge was conducted digitally through videoconferences for interviews and electronic forms previously designed by the teachers for the systematic collection of data.

Results

To carry out this research, the students uploaded the information from the database to Excel to carry out an individual study and the statistical analysis to compare the child’s interview parameters with national and international standards or recommendations. They subsequently used this information in the challenge’s second-stage activities described above. Each group (class) managed to pool and analyze the information of about 60 children.

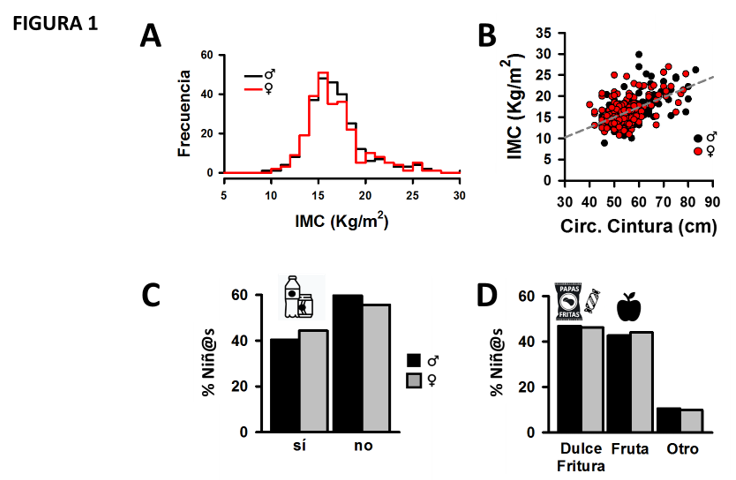

The most important achievement was that the participating students, using videoconferencing technology during the pandemic, were able to experience first-hand the importance of treating target-population tutors with respect and professional ethics. They systematically collected information from more than 600 infants enrolled in 32 kindergartens. The mean age was 5.24 ± 0.04 and 5.20 ± 0.04 for boys and girls, respectively. As shown in Figure 1, the final analysis results were qualitatively and quantitatively similar to those reported in the literature (National Institute of Public Health, n.d.; Pérez-Herrera and Cruz-López, 2019).

Figure 1. Representative final analysis results of some anthropometric data and consumption habits of sugary drinks and foods (between-meal “snacks”) were collected by the 9 groups of HS students throughout the semester.

Figure 1A shows a histogram of Body Mass Index (BMI) distribution for boys (in black) and girls (in red) based on international standards (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, CDC. n.d.). The data analysis shows that 31% of children are overweight or obese. Figure 1B shows the apparent linear relationship between BMI and waist circumference in boys and girls (the dotted line is a linear regression of all data). Factors that contribute to this problem of overweight and obesity include the high consumption of sugary drinks (Figure 1C: more than 40% of children consume them daily) and the consumption of sweets and fried foods (Figure 1D: about 45% of children consume them daily).

Reflection

The most efficient way to make the HS students aware of the magnitude of a real problem in the professional field is to discover it from within, meeting the individuals who comprise the target population. This perception is revealed in the students’ final reflections at the end of the TU (Figure 2). They manifested their level of understanding of this child health problem in our population and the social commitment they developed by addressing the challenge. In addition, the feedback from the parents of the children served by our students provided very positive information to the teachers to assess the professionalism competency developed in the training unit.

Figure 2. A) Word cloud extracted from 60 reflections of the students in the TU “Life Cycle: Childhood and Adolescence” who participated in this challenge. Figure 2. B) Examples of textual quotations from students’ reflections.

In this TU, we confirmed that individual and group work allowed a deeper understanding of the problem of child malnutrition in Mexico and the implications for the individual and society. Based on their results’ interpretation, the students proposed a variety of improvement plans, which, by their quality, reflected the success of the educational experience. Significantly, these proposals do not depend on theoretical information or foreign populations but are based on their own results, which gave them a vital component of identification and social commitment.

Finally, using digital tools such as videoconferences and electronic forms helped students overcome the barrier imposed by the pandemic and motivated them to interact and get to know the target population better.

We invite Health Sciences teachers to explore this form of teaching and document and share their experiences through publication in the Observatory of the Institute for the Future of Education of Tec de Monterrey. In this way, we all learn together and implement the best practices in our subjects so that our students have memorable learning experiences. If you have any questions or comments, leave them below in this article or write to us by email. We will gladly give a prompt response.

About the Authors

Dr. Julio Altamirano Barrera (altamirano@tec.mx) is a professor of Basic Sciences. He has worked at the School of Medicine and Health Sciences (EMCS) of Tecnologico de Monterrey for 12 years doing basic research in cardiovascular functions and teaching at the undergraduate and graduate levels. He is a member of the National System of Researchers, Level II.

Mtra. Amanda Ramos Trujillo (aramost@tec.mx) is director of the Bachelor’s Program in Nutrition and Integral Wellness and coordinator of this TU at the Monterrey Campus. She has worked for five years at EMCS as a professor at the undergraduate level.

References

UNICEF. s.f. Salud y nutrición. https://www.unicef.org/mexico/salud-y-nutrici%C3%B3n

Instituto Nacional de Salud Pública. s.f. Informe de Resultados de la Encuesta Nacional de Salud y Nutrición -2018. https://ensanut.insp.mx/encuestas/ensanut2018/informes.php

Centro para el Control y Prevención de las Enfermedades. s.f. Calculadora del percentil del IMC para niños y adolescentes. https://www.cdc.gov/healthyweight/spanish/bmi/calculator.html

Pérez-Herrera, A., & Cruz-López, M. (2019). Situación actual de la obesidad infantil en México. Nutrición Hospitalaria, 36(2), 463-469. Epub January 20, 2020. https://dx.doi.org/10.20960/nh.2116

Edited by Rubí Román (rubi.roman@tec.mx) – Observatory of Educational Innovation.

Translation by Daniel Wetta.

This article from Observatory of the Institute for the Future of Education may be shared under the terms of the license CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

)

)

)