Students have the opportunity to apply their medical knowledge and skills for the benefit of their professional development and the social welfare of their community, engaging in different roles according to the level of expertise achieved in the training process.

The COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted the Education sector worldwide, affecting the regular operation of the schools of medicine and health sciences. Unlike other disciplines, during a contingency, the teachers and students together play an active role in the work of the profession (1). Therefore, it is time to rethink the role that health professionals play while in training, not only in maintaining the continuity of their learning processes but also becoming an agent who is part of the health response.

The mission of medical schools has a formative and social purpose, considering it a fundamental idea to ensure the wellbeing of the community (2,3). On the one hand, there is a need to continue the training of health professionals with alternative methods that protect the integrity and safety of those involved, and, on the other hand, the desire to join the efforts to address the increase in healthcare needs arising from the COVID-19 pandemic.

“We are currently experiencing a transcendental moment in clinical education because, in addition to the uncertainty that the medical student typically faces during an educational procedure, he or she has to face the fear of contagion and disease during the health contingency for COVID-19.”

While some students who have well-developed professionalism and high social commitment may express a desire to collaborate during the crisis, a patient-centered approach involves ensuring that they have professional competence, safety, and efficiency through each of the phases of care: a) knowledge about the patient, b) diagnosis, c) intervention, and d) follow-up (7). For this reason, there is a need to review the requirements for their participation, not forgetting that, for all the healthcare team (including students), the patient is the first responsibility.

Along these lines, the Mexican Association of Faculties and Schools of Medicine (5) and the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) (6) pronounced themselves temporarily recommending the suspension of clinical activities in hospital areas for the students of medicine and health sciences taking courses for the bachelor’s degree.

The universities that have retired the students from the clinical activity must design an action plan and implement strategies to train students with the preparation they need to rejoin the health team in later stages of the contingency (4,8). It is essential to consider that, due to the seriousness of the health crisis, staff in training become a professional reserve that could take action if a shortage of health personnel arises. (4).

The role of health sciences students during the COVID-19 pandemic

Pre-clinical years

In the pre-clinical years, the learning activities are mainly performed in the classroom. This group of students has less risk of exposure compared to those in the stages of learning in the clinical areas. The transformation to a remote educational model allows partial or complete academic continuity, depending on the available resources. At Tecnologico de Monterrey, through the Digital Flexible Model (MFD), the professional curriculum of the health sciences students in our institution is continuing.

The commitment to society and the social responsibility assumed by the profession for the common good are intertwined. The students, as part of the health team and also future professionals, have the opportunity in situations like the current one to become included fully. Possessing medical knowledge and competencies brings great responsibility and the opportunity to engage in other roles that benefit both their professional development and the community. In different universities in Europe and the United States, the students are the ones who have played various roles of value while participating voluntarily to support the health system and its community (9,10).

Likewise, they must continue their theoretical and clinical training through the review and analysis of pandemic cases. It is a unique opportunity for discussion and feedback from students and health teams, through problem-based learning models using evidence-based medicine techniques (11,12). Simulations can also play an essential role in continuing the development of clinical competencies, including emotional skills. (13)

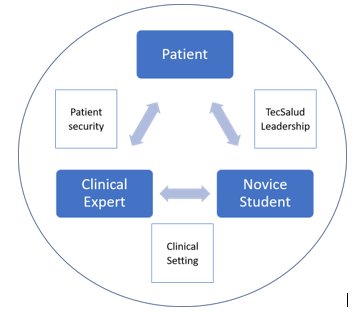

Long’s strategy (14) is shown in Figure 1 with the possible roles the student can exercise and the requirements for the development activities to fulfill in each position to provide benefit to all the participants. The students fulfilling these activities in their formative stage require constant supervision and guidance from a professor.

The different roles of medical students

Fig. 1. Diagram of the student roles and the suggested requirements for activities to be performed, based on the environment. Adapted from Long’s strategies (14).

Activities to perform during the quarantine

A. Support the dissemination of scientifically-based information that can inform the population about disease prevention measures. Include strategies for nutritional, physical, and emotional wellness during the period of isolation. (15)

B. Create national and international databases of activities in which students work to support health teams and share it with other students in schools of medicine (16).

C. Create support teams for students that mitigate the physical and social impact of isolation. (17) Create groups with diverse functions like sessions for virtual academic counseling, meetings for emotional support, a network “Check-in” system for classmates who want to ensure the wellbeing of each other, as well as other initiatives organized by students for students.

D. Parallel support: In some universities, students have implemented support programs that have excellent value for the health teams and can be done safely such as campaigns to collect masks, face covers, and protective equipment, call centers for questions and resource information, and daycare centers for children of health workers, among others. (15)

E. Clinical discussion groups: To continue the development of clinical competencies related to critical thinking and decision-making, encourage students to review, analyze, and discuss current clinical cases arising from the pandemic. This systematic review of available scientific evidence can update the healthcare professionals on the front lines of patient care. (10.11)

For the success of these activities, it is suggested to create work teams that include the presence of student leaders in the creation, planning, and implementation of the initiatives and enthusiastic teachers to guide them. The empowerment of students and how they are introduced to the rest of the student population and faculty will impact their success.

Clinical years

Starting from the questions of how clinical education and student participation can be developed in a clinical environment (hospital or ambulatory) in a full health contingency, and what is the involvement of the students in these clinical settings, we make the following observations and recommendations written below.

Fig. 2. Tecnológico de Monterrey forms leaders, not only in medical science but also leaders in society, sensitive to human pain, and busy improving or contributing to the wellbeing of patients.

Clinical Education

Clinical education is a highly complex process involving different characters: the professor (clinical expert), the student (student in clinical rotations), the environment (any clinical scenario), and the patient (the reason for the teaching-learning process). See Fig. 2. This is a dynamic process in which there is a permanent interrelationship among these characters, who routinely find themselves strongly influenced by uncertainty. It is a dynamic in which human emotions intervene significantly in the results: the demand for the safety of the patient, high-quality medical care, a solid foundation of knowledge in medical sciences, and a high level of intelligence and emotional maturity. All this reflects in the social commitment that medical students acquire as they progress in their academic advancement.

The primary characteristic of clinical education is that it develops in real environments, which can range from a first-contact consultation with the patient in outpatient settings to care in hospital, surgical, critical care units, and emergency room environments. In the article, “I prepare to help: Response of the schools of medicine and health sciences to COVID-19,” Valdez (4) mentions that, depending on what stage of training the students are in, the degree of responsibility and decision-making the students have in a clinical setting varies. Therefore, the analysis of student participation during contingency should be based on the academic grade and the level of proficiency in clinical competencies that the students present.

The position of higher education institutions regarding the return of medical students to clinical rotations in hospital systems during the COVID-19 health contingency

Students who rejoin clinical settings (ambulatory and hospital) must comply with the necessary safety measures that derive from three basic training units:

-

Previous training on COVID-19.

-

Training on the use of Personal Protective Equipment (8).

-

Training about the dynamics, logistics, and functioning of health care teams in the various hospital services. There also must be systematic rules and procedures that ensure the orderly participation of the students according to their level of professional preparation.

All training should fall under the umbrella of the school in collective agreements with the health institutions where the clinical rotation settings are located. These agreements should cover how the healthcare institution will provide adequate personal protective equipment to all the students who participate in patients care.

The article, “Guidance for medical students participating in direct patient contact activities” published by the AAMC (6), says that student participation should be based on local epidemiological considerations, the need and availability of personal protective equipment, and adequate coverage for the professionals who are working directly with infected patients. Another element to consider is the availability of tests (diagnostic and confirmatory) for COVID-19. Supervision, observation, and medical care for the students should be ensured during their participation equal to any other member of the health team.

The participation of students in the initial or advanced stages may be developed if there are: 1) availability of personal protective equipment, 2) guarantee of protection, supervision, observation and monitoring for the overall wellbeing of the student, and 3) availability of health care through the school health departments, medical insurance, and access to institutional or public health services(if required).

In this document, we have classified clinical science students into two groups, according to their grade (year) in the university:

-

Students in the initial stage of clinical training (those who have not completed all the core rotations in surgery, internal medicine, gynecology and obstetrics, and pediatric services).

-

Students in the advanced stage of clinical training (those who have already completed the four core courses and are in the terminal rotations).

Classification of students in clinical sciences

1. The first level of care: students in the early stages of professional clinical training

Students in the early stage of their clinical practice will be able to participate in the first level of care as they have the necessary clinical and medical tools to:

-

Support the education and promotion of the health of the general population, educating them about hygiene and cleaning measures that can prevent infection and contagion, ss well as provide information about the disease and its potential consequences.

-

Lead the vital task of debunking false information and preventing its spread. The proliferation of fake news and rumors is a new factor in the public health arena that students at this stage can combat.

-

Analyze, catalog, summarize, and sort the vast information that emerges every day about the pandemic. Hundreds of articles, protocols, guides to managing the disease, news, and reviews are published every week. Students have the necessary tools to design and build information repositories on which health institutions can rely for the decision-making.

-

Detect suspicious cases early and timely. Educate the population about the clinical warning signs so that they will seek medical attention.

-

Refer cases with risk factors or complications early. The student can detect, even with remote triage, relevant signs, and symptoms to decide to refer the patient to the second or third level of care.

-

Care for and protect the population, making patients feel secure in the information received and under close surveillance; reminiscent of the family doctor’s involvement in the old days.

-

Apply quick diagnostic tests, as long as the student is adequately trained and has the necessary safety measures and equipment.

-

Actively participate in the identification of accurate, evidence-based information about the pandemic while generating audiovisual or textual content that can be disseminated through various means of communication. Do not oversaturate the general public with information on the epidemic; instead, contribute responsibly to the dissemination of educational material for the general population and health personnel.

2. The second and third levels of care: students in the advanced stages of professional clinical training

The student activities should be taught and supervised by a clinical expert, ensuring their safety with appropriate personal protective equipment. Their participation is primarily regarded as an observer of the process without hindering its dynamics. The student may be guided by following the actions of his/her tutor and the experts who are treating potentially infected patients. To identify the reasoning mechanism that leads students to make decisions about diagnoses and therapeutic measures, the students should follow a clinical-pattern-observation algorithm that will support the experts attending the patients, when the tutor considers this appropriate. Also, one can:

-

During the medical act, be an emotional support to the expert. At this time, the student will be able to develop skills of resilience, empathy, and leadership by contributing positively to the medical attention being delivered.

-

Develop and improve doctor-patient communication by observing and communicating with the family members and to the patients themselves.

-

Participate in obtaining the sample for diagnosis, being duly trained with the necessary safety measures and equipment, and, thus, playing an active role in the tasks of the health team to which the student belongs.

-

Participate in the recording of the actions taken during the shift.

-

Follow-up patients remotely who are diagnosed with COVID-19 but do not require hospitalization. Support the patients and their families and the expert professionals through follow-up reports that allow the expert caregivers to know the situation of these patients. The students can develop and strengthen clinical knowledge about respiratory monitoring and detect data that indicates respiratory failure as well as data that could alert the caregiver about systemic deterioration that would require the patient’s transfer to emergency medical hospital care.

-

Remotely follow-up discharged inpatients who are at home finishing the recovery phase of the disease.

Recommendations regarding returning the students to clinical activities

We are currently experiencing a transcendental moment in clinical education because, in addition to the uncertainty that the medical student typically faces during an educational procedure, he or she has to face the fear of contagion and disease during the health contingency for COVID-19.

Recommendations before the re-incorporation

-

Support from the academic institution to the student through the creation of a National and Regional Collegiate Body that supervises the students’ participation and their follow-up.

-

Check the students’ mental health status before their reinstatement, looking for signs of depression and anxiety, in order not to expose them to emotional or psychiatric deterioration when subjected to stress during their clinical rotations.

-

Close monitoring of the physical and mental health of the students by both the educational institutions and the hospital institutions.

-

The supervision of students during their reintegration into clinical settings during the pandemic should be a shared commitment among educational institutions and health institutions.

-

Check that the students have the minimum clinical competencies required for their participation through evaluations and certifications of various educational institutions that document the management of these skills.

Required minimal clinical competencies

-

Medical knowledge

-

Manual skills to perform basic physical examination procedures

-

Taking of samples

-

Training in behavior and mobility in a COVID-19 hospital. This is for the student to develop competencies related to the use of personal protective equipment, physical examination of a potentially infected patient and a patient with COVID-19, COVID-19 physio-pathology and clinic, and understanding how he adds to the care team.

With these competencies, the student will present himself as a resource to support the team of healthcare professionals involved in inpatient care.

If these primary conditions are ensured, as well as the safety guarantees for students by health institutions, the reinstatement of the medical students will be crucial to the improvement in the capacity of medical care provided to patients. It also provides students with personal and professional life experiences while increasing their medical knowledge. It will allow them to have a background that is part of their educational experience, with meaningful learning that they can use in future situations with similar conditions.

The participation of students of the Surgeon Physician program in the advanced training stage of Clinical Sciences in the health care process during the COVID-19 health contingency marks a significant opportunity and distinction from the care and response models of the educational institutions: The opportunity lies in generating professionals who are part of a health team, who have a humanist training, who are responsible, socially committed, and ethical during a disaster or emergency of these dimensions. The reinstatement of students to clinical areas should be very carefully supervised by a tutor and the educational institution, taking on the responsibility to recognize that students are confronting an extraordinary training opportunity for their professional and personal development.

Conclusions: benefice, autonomy, and social responsibility

In conclusion, we find ourselves faced with a situation that demands an extraordinary expression of the fundamental ethical and professional duty of every medical professional: the primacy of benefice to the patient and the social responsibility of the profession to procure the right to health. This is a historical opportunity for medical students to claim their roles by demonstrating that they are active and relevant members of the health team, assuming their responsibility for service in times of crisis, and standing in solidarity with the profession (18).

About this, Gallagher and Schleyer (19) address the question of how we should balance the imperatives of clinical care and education with those of the wellbeing and safety of the students. Faced with uncertainty and frustration at the loss of traditional educational experiences (20), the students in medical education institutions today have the alternative of being innovative. They can generate new environments and strategies to achieve not only the personal interests of vocational training but also the professional, ethical acts of commitment and responsibility for the common good.

The students, every one of them, have the full right to self-determination and the exercise of their autonomy. They will have to decide responsibly whether they contribute to building a new bridge between the development of their professional competencies and patient care in the current pandemic environment of health systems in crisis (16). They must explore with creativity, innovation, and flexibility, with responsibility and courage, and without

giving up their wellbeing and personal integrity. You can check the full version here.

About the authors

Jorge E. Valdez-Garcia (jorge.valdez@tec.mx) is Dean of the EMCS, with 25 years of undergrad and graduate teaching experience. He is a researcher in SNI, level 1, in health sciences. Author of 3 books, ten chapters, and more than 80 research articles. Academic Holder in the Mexican Academy of Surgery. Vice President of AMFEM (Mexican Association of Faculties and Schools of Medicine).

Irma E. Eraña-Rojas (ierana@tec.mx) is a Surgeon specializing in Pathological Anatomy by coursing the Fellowship in Health Professions Education: Accreditation and Assessment (FAIMER). She is an Associate Fellow for the Association for Medical Education in Europe (AMEE) and a professor of Pathology and Director of the Surgery curriculum at Tecnológico de Monterrey on the Monterrey campus.

José A. Diaz Elizondo is a Surgeon specializing in General Surgery with a subspecialty in Advanced Laparoscopy, recertified for the fourth time by the Mexican Council of General Surgery. Ph.D. in Clinical Sciences, participating in research projects with the School of Engineering and the School of Medicine at Tecnológico de Monterrey. Director of Clinical Sciences at the School of Medicine for the North Region.

Mary Ana Cordero-Díaz is a Surgeon in the School of Medicine at Tecnológico de Monterrey. She has a Diploma in Advanced Studies and Research Sufficiency in Humanities with a specialization in Moral Philosophy from the Carlos III University of Madrid. Teacher and Coordinator of the Program for Professionalism and Wellbeing in Medical Specialties.

Alejandro Torres-Quintanilla is a Surgeon with a Master of Science in Biotechnology and is pursuing a doctorate in Biotechnology. Professor of Physiology at the School of Medicine and Health Sciences at Tecnológico de Monterrey on the Monterrey campus.

Lydia Zeron-Gutiérrez is a Surgeon with a master’s and Ph.D. in Health Sciences in Medical Education from the Faculty of Medicine of Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM). Her line of research: Continuous Professional Development. Undergraduate and graduate professor. Director of the Department of Clinical Sciences at Tecnológico de Monterrey on the Mexico City campus.

References

1. Juan Pablo Beca I, María Inés Gómez B, Francisca Browne L, Jorge Browne S. Los estudiantes de medicina como parte del equipo de salud. Rev Med Chil. 2011;139(4):462–6.

2. Riquelme Pérez A, Püschel Illanes K, Díaz Piga L, Rojas Donoso V, Perry Vives A, Sapag Muñoz J. Responsabilidad social en América Latina: camino hacia el desarrollo de un instrumento para escuelas de medicina. Investigación en Educación Médica. 2017;6(22):135.

3. Puschel K, Rojas P, Erazo A, Thompson B, Lopez J, Barros J. Social accountability of medical schools and academic primary care training in Latin America: principles but not practice. Family Practice. 2014;31(4):399-408.

4. Valdez, V., López, M., Jiménez, M., Díaz Elizondo, J.A., Dávila Rivas, J.A., Olivares, S. (2020). Me preparo para ayudar: respuesta de escuelas de medicina y ciencias de la salud ante COVID-19. Inv Ed Med. Vol. 9, n.o 35, julio-septiembre 2020. Retrieved the 22 of April https://doi.org/10.22201/facmed.20075057e.2020.35.20230

5. Asociación Mexicana de Facultades y Escuelas de Medicina. Comunicado importante Covid-19 [Internet]. Amfem.edu.mx. 2020 [citado 25 Marzo 2020]. Available at: http://www.amfem.edu.mx/index.php/acerca/comunicados

6. Whelan A, Prescott J, Young G, Catanese V. Guidance on Medical Students’ Clinical Participation: Effective Immediately [Internet]. Association of American Medical Colleges. 2020 [cited 25 March 2020]. Available at: https://www.aamc.org/system/files/2020-03/Guidance%20on%20Student%20Clinical%20Participation%203.17.20%20Final.pdf

7. Olivares Olivares SL, Jiménez Martínez MA, López Cabrera MV, Díaz Elizondo JA, Valdez-García J. Aprendizaje centrado en las perspectivas del paciente: el caso de las escuelas de medicina en México. Educación Médica. 2017;18(1):37-43.

8. Whelan A, Prescott J, Young G, Catanese VM, McKinney R. Interim Guidance on Medical Students’ Participation in Direct Patient Contact Activities: Principles and Guidelines [Internet]. Association of American Medical Colleges. 2020 [cited 22 Abril 2020]. Available at: https://www.aamc.org/system/files/2020-03/meded-March-30-Interim-Guidance-on-Medical-Students-Clinical-Participation_0.pdf

9. Krieger P, Goodnough A. Medical students, sidelined, for now, find new ways to fight coronavirus. New York Times. March 23, 2020. Accessed April 5, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/23/health/medical-studentscoronavirus.html

10. Kaschel H. Coronavirus: In Germany, medical students step up to fight COVID-19 [Internet]. Deutsche Welle. 2020 [cited 2020 Apr 23]. Available from: https://www.dw.com/en/coronavirus-in-germany-medical-students-step-up-to-fight-covid-19/a-53019943

11. Sánchez-Mendiola M, Lifshitz-Guizemberg A, Esperón-Hernández R; Medicina basada en evidencias y análisis crítico de la literatura médica. En: Educación Médica: Teoría y Práctica. Edit. Elsevier, España, 2015. ISBN: 9788490227787.

12. Esperon-Hernandez R.I. Desarrollo de Competencias para la toma de decisiones médicas basadas en la evidencia en estudiantes de medicina de pregrado. Universidad de Granada, España, 2014. ISBN: 978-84-9028-991-4 Available at: https://digibug.ugr.es/bitstream/handle/10481/32131/23539306.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

13. Esperón Hernández R.I; ¿Las Escuelas de Medicina se deben ocupar en las competencias emocionales de sus estudiantes? Rev Inv Ed Med, 2018; 7 (26): 10-12. Available at: http://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?pid=S2007-50572018000200010&script=sci_arttext&tlng=en

14. Long, Gon

zalo et al. (2020) Contributions of Health Profession Students to Health System Needs During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Strategies/Process for Medical Schools. Under Review.

15. Carlson, S., Gonzalo, J., Hammoud, M., Havemann, C., Lomis, K. (2020). Deploying Students in alternative roles during COVID-19: Preserving clinical educational objectives and supporting competency development. AMA Innovations in Medical Education Webinar Series. Recovered el 22 de abril de 2020 en: https://cc.readytalk.com/cc/playback/Playback.do

16. Task Force Database [Internet]. [cited 2020 Apr 22]. Available from: https://covidstudentresponse.org/resources/taskforce-database/

17. Murphy B. Online learning during COVID-19: Tips to help med students succeed. American Medical Association. 2020. p. 1–5 [internet]. Association of American Medical Colleges. 2020. Available from: www.ama-assn.org/residents-students/medical-school-life/online-learning-during-covid-19-tips-help-med-students

18. Gibbes Miller, D.; Pierson, L.; Doernberg, S. (2020). The Role of Medical Students During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Ann Intern Med. DOI:10.7326/M20-1281

19. Gallagher, T. y Schleyer, A. (2020). “We Signed Up for This!” — Student and Trainee Responses to the Covid-19 Pandemic. NEJM April 8, 2020, DOI: 10.1056/NEJMp2005234

20. Hill, M., Goicochea, S., Merlo. M. (2018). In their own words: stressors facing medical students in the millennial generation. Medical Education Online, 23:1, DOI: 10.1080/10872981.2018.1530558. Retrieved the 22nd of April: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/10872981.2018.1530558

Editing by Rubí Román (rubi.roman@tec.mx) – Observatory of Educational Innovation.

Translation by Daniel Wetta.

This article from Observatory of the Institute for the Future of Education may be shared under the terms of the license CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

)

)

)