High school education does not have a transitional chapter between primary-level Civics education and professional political science training.

In previous articles, we have written about the fundamental right to education in Civics to understand how the government works under which we live. However, this year has presented new situations exposing the crucial need to educate the citizenry about the exercise of democracy.

The elections in the United States were a strenuous process for the citizens of one of the most powerful countries in the world. The rest of the planet also tuned in to know the results of one of the most critical elections in United States history. Observing the drama of the event and its aftermath, we must consider that in this case, and many others worldwide, social factors influenced the voters as much, or more than, their political leanings.

The public conversation surrounding the American vote did not focus on wanting a left-or-right-wing government, one tax package over another, or a specific health education plan. In the United States, the people voted based on their stance toward an economic plan in the face of the present health crisis, whether or not they believed in the need for a movement like Black Lives Matter, the freedom of women to have reproductive rights, the mitigation or cancellation of student debt, universal health coverage provided by the federal government, or their right to bear arms.

On many occasions, during discussions of the U.S. election, the general feeling was that people were voting to elect candidates who defended their interests in matters of life and death. Repeatedly, the press and social media characterized the elections as “A Battle for the United States “soul.” How can an electoral process become so critical?

No transition from Civics to political education

Primary-level Civics education goes hand in hand with ethical training. Children are taught the basics, learning where society’s laws and rules originate, and a fundamental idea of how their government system works.

After this phase, in which they learn about their obligations, powers, and citizen rights in their countries, education in this area stops. Therefore, know how to exercise their roles in democratic government, young people learn about how, when, and why to vote from their families, the press, and the candidates themselves through their advertising and propaganda. However, they receive little or no academic training on the subject.

There is no intermediate level between primary and high school Civics education and a major in undergraduate Political Science that enables students to understand political inclinations and governments and candidates’ plans at all levels. In this absence of knowledge, young people and adults with voting rights rely on other criteria to decide their votes.

The profound complexity of voting in the United States

The recent elections in the United States are a map for understanding how an average citizen’s vote works in a democratic system. In 2016, Donald Trump got his first and final presidential term and the show Jimmy Kimmel Live! performed a dynamic in which one of his correspondents casually asked passers-by what it would take for the Republican magnate to lose his vote.

The Republican voters’ responses left a clear idea of how the general public approaches political issues. According to a U.S. Political Science Review article, only 3.5% of the U.S. voters would change their vote if the candidate they favored did or said something that would damage the basis of a democratic system.

This might seem inconceivable to citizens of a country with a democratic form of government, but the United States’ case is very particular. If we were to talk about Mexico, by comparison, all citizens 18 years and older only have to process their credentials in the National Electoral Institute to be on the voter registry and vote in all elections pertinent to the area where they live. In the United States, not all adults with identification have access to the vote.

One of the most relied upon official identification cards of the United States’ citizens, the driver’s license, does not entitle them to vote; the ability to vote in an election requires a specific voter registration in a county’s voting district or city where they live. Although the voter registration system was established under civil rights acts to protect the right to vote for disenfranchised minorities, in many historical cases, the majority population has made the process complicated to deprive the vote of people from social and economic minorities. To prevent fraudulent voting by “fictitious” persons, an essential function of voter registration has been abused historically to make voting complicated for the socially disenfranchised.

In 2016, only 64% of US citizens eligible to vote actually voted. Though this percentage seems low, it was higher than many historical elections. In the current year, the number of people registered and eligible to vote and who actually voted increased to 67% as minorities and culturally diverse groups mobilized voters to defeat Donald Trump. Still, this means that one-third of the U.S. citizens who are eligible to vote did not do so and missed out on the opportunity to choose their public servants.

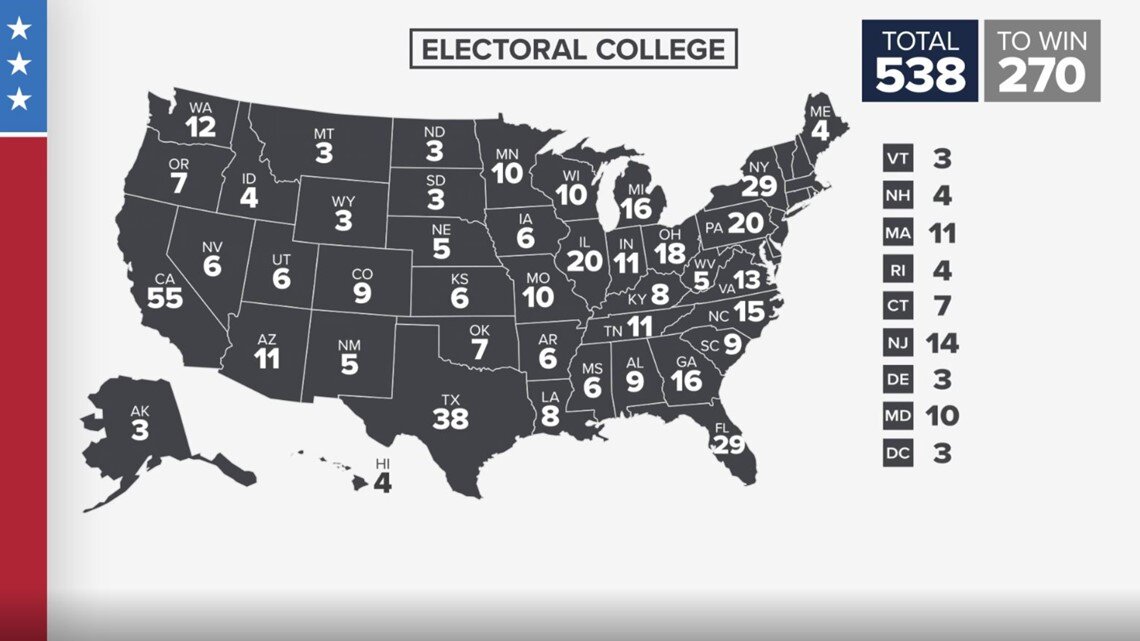

There are other complexities characteristic of American democracy, such as the Electoral College, which means that the United States is a republic and not a pure democracy. The President and Vice-President are elected by members of the Electoral College in each state. Each state has a proportional number of Electoral College votes determined by the state’s population as a percent of the nation’s population. Therefore, the people called the “popular vote” votes do not directly elect the President per se. The candidate who wins the popular vote wins all of that state’s Electoral College votes in each state. The most populous states have the most representatives in the Electoral College. For example, California has 55 votes, Texas 38, Florida 29, while states like Montana, North Dakota, and Wyoming have only 3.

Electoral college map. Source: 11Alive

Therefore, it has happened that a President can have fewer votes nationwide in the popular vote and still be elected. This was the case in 2016 when Hillary Clinton had 3 million more votes nationwide than Donald Trump. In 2020, Joe Biden has over 7 million more nationwide votes than Donald Trump.

Adding even more complexity to the United States’ electoral process is gerrymandering, which has historically caused contrived chaos in U. S. elections. The term refers to the manipulation of constituencies in a territory to favor or disadvantage a political party. In gerrymandering, the boundaries of voting districts are changed by the parties in power to affect the populations who vote in those districts. Throughout the history of U.S. elections, districting and redistricting have significantly affected local, state, and federal elections for both Democrats and Republicans.

This year, one of the most dramatic aspects seen in the U.S. elections was the voting times. In Georgia, voters waited in a line approximately eleven hours to exercise their right to suffrage; Texas recorded a maximum of eight. Much of this was due to the differing regulations in states to facilitate voting during the confinement caused by the pandemic. This situation caused some chaos and confusion in the weeks before Election Day. A record number of voters in the United States voted early as a result. By Election Day, over 70% of U.S. voters had already voted. By comparison, countries such as England, Estonia, India, New Zealand, and Australia average 1 to 10 minutes to place their votes as citizens.

Not all democracies have the degree of complexity as the U.S. system, but electoral mechanisms like those in the U.S. system manifest the need for continuous ethical education as a political education foundation.

Practices such as the exclusion of voters which disproportionately affects a social or economic sector, the ability of public servants to manipulate district boundaries for their benefit or political party, the imposition of laws, regulations, and processes that make it extremely difficult for many voters to exercise their suffrage, are all political and ethical matters that directly affect how, when, why and in what capacity people vote.

Even if these problems are not identical in democracies in other countries, each political system has its endemic infirmities to treat. That is why a political education that complements Civics is crucially important for integral citizenship and a democratic system that works in both theory and practice. Do you think that political education is necessary for citizens to exercise their rights fully and have a better equilibrium of democracy? Tell us in the comments.

Disclaimer: This is an opinion article. The viewpoints expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the opinions, viewpoints and official policies of Tecnológico de Monterrey.

Translation by Daniel Wetta.

This article from Observatory of the Institute for the Future of Education may be shared under the terms of the license CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

)

)

)