“Challenge-Based Learning used in forensic medicine and pathology is somewhat novel. The students were excited to live an experience full of uncertainty, adventure, and challenge.”

This is a popular article made in collaboration with Tecnológico de Monterrey’s Writing Lab.

Can you imagine learning in the style of the famous original television series, “CSI: Crime Scene Investigation,” where forensic scientists and criminologists work together to solve mysterious crimes by analyzing data, evidence, and scientific tests state-of-the-art technology to solve the cases that arise? Well, the professors at Tec de Monterrey (TEC) made this possible. With the leadership of Dr. Irma Eraña-Rojas and the counsel of several teachers who participated in this practice, the students worked in multidisciplinary teams in simulated “crime scenes.” Students had to identify relevant evidence at the crime scene, possible crime-scene alterations, and alleged victims and perpetrators. This exercise is part of their professional training in knowing the elements that lead to best-quality forensic science.

In this week-long educational experience, the students took on the challenge of analyzing the processes performed by experts in the Institute of Criminology and Expert Services and the Forensic Medical Service of the State of Nuevo León, Mexico. The educational approach used in this activity was Challenge-Based Learning (CBL), a pedagogical strategy that exposes students to real-life situations where uncertainty is high, and their previously acquired knowledge is challenged (1).

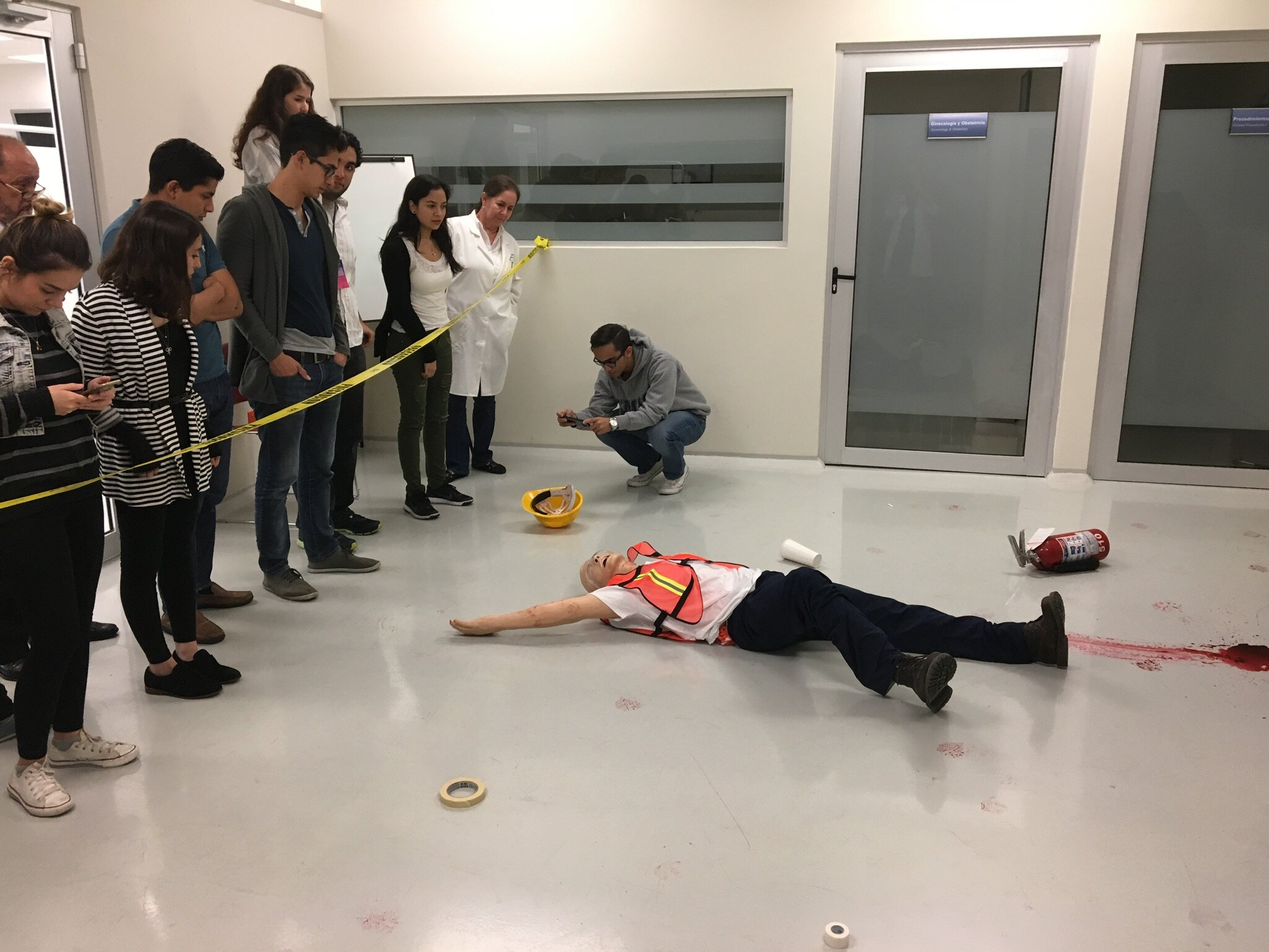

Image 1: Example of a crime scene simulation using a mannequin.

The implementation of Challenge-Based Learning in forensic medicine and pathology is somewhat novel because these sciences’ fundamentals are usually acquired through theoretical classes. Therefore, the teaching team’s challenge was to build multiple activities from conferences with specialists, simulated practices, and visits to various expert research areas. Clinical simulations using photos, augmented and virtual reality, mannequins, robots, and standardized patients as tools provide an excellent alternative for learning forensic autopsy (2).

“88.9% of the students who participated in this educational experience considered that it broadened their perspective on forensic sciences, and 73.1% think that this practice added value to their academic training.”

The students confronted their challenges through multidisciplinary teams from the Schools of Medicine, Law, and Marketing and Engineering, thus, developing innovative, interdisciplinary transversal competencies. The pedagogical design included a balance of theoretical sessions (modules) and practices (the challenge resolution) both in the facilities of Tecnologico de Monterrey and the Forensic Medical Service of the State of Nuevo León.

At the beginning of the activity, the students were skeptical but excited to be in a real-world type of experience, a mixture of uncertainty and adventure. However, all had a strong willingness to experience a situation that would lead them to learn or apply new concepts innovatively. In the final survey, 88.9% of the students considered that this experience broadened their perspective on forensic sciences, and 73.1% indicated that this practice added value to their academic training.

Image 2: Students analyze the crime scene using a mannequin.

The main goal was that the students would understand the complexity of managing a crime scene. Being a forensic investigator involves police presence at the scene, the search for biological specimens and documentation of its testing, photographs, sketches and diagrams of the scene, final storage of evidence, the establishment of the chain of custody, and preparing the forms for the investigative report.

“The students had the opportunity to evaluate themselves by testing their previous knowledge to solve a specific challenge.”

During the intensive training, the students participated in drills, interviewed medical specialists who participate in forensic autopsies, and made visits to different government agencies to understand the processes involved in a formal investigation. For CSI-LAB deliverables, the students produced videos of their solutions to the forensic medicine challenges, proposals, and feasibility assessments. Professor-experts from various areas evaluated the proposals. Their perception of the students was excellent.

This experience provided many lessons to both students and professors. Students had the opportunity to self-assess by putting their previous knowledge to the test, solving a specific challenge. It provided the professor with new ways to transmit knowledge by analyzing a challenge, new forms of collaborative and multidisciplinary work, and a new role as a co-researcher to resolve the challenge. This new modality requires professors to devote more attention to developing the tools, instruments, and learning techniques.

The Tec21 Educational Model of Tec de Monterrey has revolutionized the way of teaching in the world. The transition from a face-to-face classroom to an immersive, rich, and authentic educational environment in the real world requires developing new skills. Tec21 model stands on four fundamental pillars:

-

Flexibility (where and when to learn).

-

Inspiring teachers (experts up to date with digital tools).

-

Memorable experience (a comprehensive education).

-

Challenge-based learning (CBL).

Dr. Eraña-Rojas’ class originally published this article in one of the field’s highest impact journals, Medical Education (a Q1 journal), in the exclusive section, “Really Good Stuff“(3). It led to the subsequent expansion of the research and conclusions. A larger version of the research work was published in the world’s leading journal of forensic medicine, the Journal of Forensic and Legal Medicine (Q1; 4). According to the SCOPUS index database, these publications received five international group citations in Germany, China, and England just one year after publication, demonstrating their resonance and impact.

This experience shows that the CSI-LAB was an excellent didactic proposal in medical education that was an essential component of the Tec21 Educational Model implementation.

This article is an adaptation of a publication in a special issue about education in the Journal of Forensic and Legal Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jflm.2019.101873

About the authors

Irma E. Eraña-Rojas (ierana@tec.mx) is a Surgeon specializing in Pathological Anatomy. She is pursuing a Fellowship in Health Professions Education: Accreditation and Assessment (FAIMER), an Associate Fellow for the Association for Medical Education in Europe (AMEE), and professor of Pathology and the Medical Director Surgeon Program at Tecnológico de Monterrey, Campus Monterrey.

Mildred Vanessa López Cabrera (mildredlopez@tec.mx) is Director of Innovation and Educational Research at the School of Medicine and Health Sciences. She holds a Ph.D. in Educational Innovation, a fellowship from the FAIMER Institute (Foundation for Advancement of International Medical Education and Research), and the Pontifical Catholic University of Chile.

Elena Ríos Barrientos (elena.rb@tec.mx) is Medical Surgeon at Tecnologico de Monterrey. She specializes in Forensic Medicine (IPN) with a subspecialty in criminal anthropology. Instructor in Clinical Simulation at CMS-Harvard-Virtual Hospital, Valdecilla. Professor and National Director of Clinical Simulation. Ten years of experience in clinical simulations.

Jorge Membrillo Hernández (jmembrillo@tec.mx) is a Biotechnology professor at Tecnologico de Monterrey, Mexico City Campus. Postdoctoral: Harvard Medical School. Ph.D. in Biotechnology: King’s College London. BSc. in Biomedical Research: UNAM. Dr. Jorge Membrillo’s interest is implementing courses under the Tec21 Educative Model using the Challenge-Based Learning technique.

References

1. Observatory of Educational Innovation of Tecnologico de Monterrey. Challenge-based learning. Monterrey: Available at http://observatorio.itesm.mx/edutrendsabr/.

2. Jones R.M. (2017). Getting to the Core of Medicine: Developing Undergraduate Forensic Medicine and Pathology Teaching. J. Forensic Leg. Med. 52:245–251. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jflm.2017.10.006.

3. Eraña-Rojas, I.E., López-Cabrera, M. V., Ríos-Barrientos, E., Membrillo-Hernández, J. (2019). A context-rich educational experience through crime scene analysis. Medical Education. “Really Good Stuff: Lessons learned through innovation in medical education.” 53:1138-1139. https://doi: 10.1111/medu.13989

Eraña-Rojas, I.E., López-Cabrera, M. V., Ríos-Barrientos, E., Membrillo-Hernández, J. (2019). A challenge-based learning experience in forensic medicine. J. Forensic Leg. Med. 68:1-5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jflm.2019.101873

Edited by Rubí Román (rubi.roman@tec.mx) – Observatory of Educational Innovation.

Translation by Daniel Wetta.

About Writing Lab

The Writing Lab is a TecLabs initiative dedicated to the development of the culture of research in educational innovation and the improvement of the academic production of the teaching community at Tecnológico de Monterrey.

Financing and technical support are provided only for Tec de Monterrey’s professors to attend conferences or publish articles in journals.

For more information visit: https://writinglab-tec.com/

Facebook: http://facebook.com/WritingLabTEC

Twitter: @TecWriting

Instagram: instagram.com/writinglabtec/

This article from Observatory of the Institute for the Future of Education may be shared under the terms of the license CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

)

)

)