Scientific research in social sciences allows us to know the world from a different perspective. It involves delving into the perspectives and experiences of individuals, studying social, political, and cultural movements and phenomena, and analyzing historical facts that identify or mark us as humanity. Those dedicated to carrying out this type of research feel motivated to understand how our social ecosystem works. What is people’s individual or group behavior even when they think very differently? Why do we make certain decisions and not others? These are among many other questions.

Conducting research within the framework of social sciences involves reflection, reasoning, analysis, and decision-making that go beyond choosing specific strategies for data collection and analysis. A key piece is to reflect before making methodological and technical decisions. Therefore, university professors must develop research skills in students, such as inductive and deductive reasoning, problem-solving, and analytical thinking. The aim is that students can apply them within the classroom when putting together a research project and when making decisions throughout life.

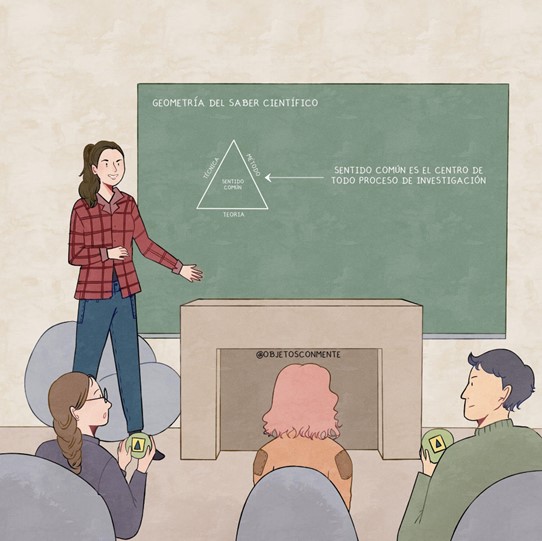

“The geometry of scientific knowledge” is a pedagogical proposal to conduct research in social sciences. It enjoys the privileges of geometric figures and their attributes to bring the abstract and non-manipulated to something concrete and visible.

Scientific ways to know the world, others, and ourselves

There are several scientific approaches to learning about the social world. The most dominant and renowned in undergraduate or graduate level classrooms are quantitative and qualitative research. However, the methodologies can have underlying prejudices that hinder understanding phenomena. For example, some teachers keep debating the scope and limitations with one another, not paying attention to the phenomenon’s characteristics: What do we know about it? Has it been studied or not? What do the researchers say? What still needs to be understood about it? Do the numbers and topics explain enough to understand the phenomenon in-depth?

Quantitative research is considered the most pertinent when you want to conduct a study led by questions such as: What is the relationship between preparing a doctoral thesis in Mexico and the level of stress perception? A cause-effect relationship exists in these studies, and statistics express the results in numbers (interpreting what the numbers tell you). In the qualitative approach, we ask, for example: What is the experience of doctoral students in Mexico like when preparing their doctoral thesis? Here we seek the interest in knowing the perspective and experience of the individual; the emphasis is on the senses, the meanings, and the experiences; there is subjectivity.

The choice of methodological approach depends on the researchers’ interests regarding the study phenomenon (what he wants to know) and the state of knowledge on the subject (what is known about it).

Scientific research in university classrooms

From my experience as a university professor in scientific research subjects in Social Sciences, I have encountered various problems that have to do with the curriculum. My main concern is the need to propose a pedagogical culture for teaching scientific research in social sciences, ensuring that it is not reduced or limited to research methodologies (methods and techniques).

Therefore, my proposal in this article aims to contribute to this pedagogical dialogue. First of all, I intend to assist both the teacher and the student in teaching and learning social science research. A second objective is to address the apparent problem of teaching research as if it were a process of selecting methods and techniques.

Pedagogical proposal to build your social sciences research project

I designed a pedagogical resource that makes participatory and visible the components and elements usually forgotten or omitted by teachers when they teach research methodologies in social sciences and are unknown to students when they learn and undertake their research projects.

Those dedicated to this know the laborious process of teaching research methodologies in the social sciences. Besides assisting and guiding the student in formulating and approaching the problem and elaborating the research questions, we must also attend to their constant questions: How will I measure what I want to study? What standardized instruments am I going to use? How am I going to analyze and interpret what I found?

Often, these questions are seen and treated by both students and teachers as if they were the center of the research project or, worse, the only steps to answer the research question.

This proposal has two objectives:

1) assist the teacher in teaching scientific research at the university level in the social sciences, and 2) assist the students in learning science, either through creating their research project or understanding the research carried out by others.

The geometry of scientific knowledge, as I call it, enjoys the privileges of geometric figures and their attributes to convert the abstract and non-manipulable to something concrete and visible. Next, I describe each component, starting from the center outwards.

The equilateral triangle

Before moving forward, it is necessary to clarify that the positioning of the researcher or the student, in this case, is what delineates at every step. Reflexivity about your decisions becomes valuable and necessary to justify each step in the project.

Within this triangle is common sense that ignites all the ideas coming out. It is the trigger, the flame, or curiosity surrounding a particular topic. A thousand questions arise within us, but from them, we choose one, preserved in that form of common knowledge, in a context closest to our reality, our knowledge, and feelings, for example, Why do some people do good deeds, and others do not?

Just as common sense is at the center of the triangle, there is also reflexivity, as warm components that enable research: motivation, interest, and positioning (from where you ask, who you are, example: Mexican, middle social class, etc.).

For these questions to become considered scientific, they need to go through a transition of moving from common sense to scientific knowledge. It is achieved once that question (which is located in the filling of the triangle) advances towards its vertices.

If we characterize the triangle, we realize that it is equilateral, and all its angles are equal. Each vertex has a name. All three have the same weight, place, meaning, and value for transforming common sense into scientific knowledge. Their names are Theory, Method, and Technique, and together they are the famous “tripod.”

If we want the initial approach (Why do some people do good deeds and others do not? Why is that?) located in scientific knowledge, we need to advance from the theory. We must begin to review articles and books on what this phenomenon is called and what is known about it. After doing this, I might realize that “good deeds in people” can be called “prosocial behaviors” in the literature (Penner et al., 2005). Keep in mind that the choice of theory and the conceptual model is the criterion of the researcher.

Later, to continue in the process, I need to think about how I want to approach knowing this phenomenon. Am I interested in experiences, meanings, senses, and representations, or am I interested in generalizing, establishing comparisons, and trends? This reflection will lead me to decide which method to use, that is, which methodological approach would be relevant to conduct my study (quantitative, qualitative, and multimethod or mixed). Each methodological approach has its tradition and history, its ways of knowing and approaching the participants; I refer to the methods. These could be surveys for the quantitative approach, in-depth interviews in the qualitative approach, and the mixed one can incorporate both.

These three components must correspond to each other. If I give the theory a heavier value than the method or technique, the equilateral triangle will disappear. Let’s agree that the choice of theory accompanies the process of the method as to what data collection strategy we will use to operationalize the variable or when we interpret the data—for example, a scale of prosocial behaviors or a set of guidelines for conducting a semi-structured interview.

Do not forget that the same technique has its theory, which tells us how to carry out research with scientific rigor or quality criteria, and even decide the place of the theory, also known as the theoretical framework. The latter exemplifies studies with the qualitative design, where the theory arises from the data, that is, inductively (Glaser and Strauss, 1967).

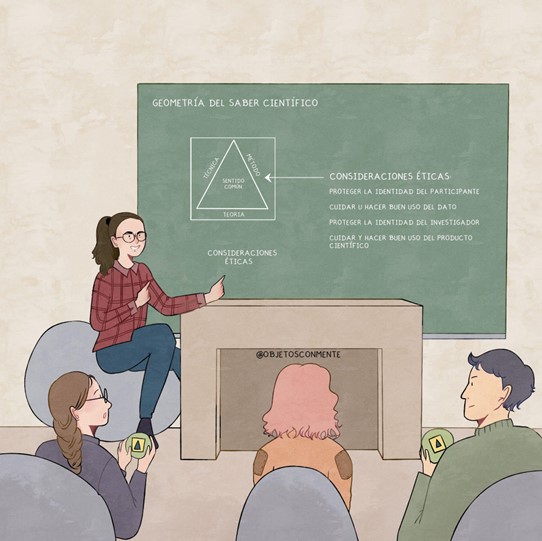

The square

As we advance in the tripod, we must think about how we approach the participants; we cannot go towards them alone. We must plan how to do it, but logistics aside, let’s focus on ethical considerations.

These ethical considerations are not only for the participant but also for the data obtained, the research, and the product (the research project). The four points give the square its shape, and we see how some of the vertices touch each other. At the top, we have the participant–data relationship. The researcher must develop a participant’s informed consent, one of the most used ethical strategies in the social sciences (Barton, 2015). This document aims to protect the participant’s identity, not using his name or elements that identify him. It should also clearly detail aspects related to the voluntariness of the subject’s participation and what it means to participate in the project (interview with a duration of approximately two hours, answer questions related to a specific topic) so that the potential participant makes the decision. As for the data, we describe its destination in the consent and how the participants’ data will be used. For example, it can be a research project for a thesis to obtain a bachelor’s degree, or the results are intended to be presented in congresses and classes. The consent should discuss where that information will be stored, how long, when it will be deleted, and how the data is protected (locked in an office, with a password on a computer).

Subsequently, we consider the researcher-product, where care is taken not to plagiarize other scholars, recognizing the merit and contribution of each; thus, the system of references and citations (APA, for example) is used for this. Also, we consider how our research product contributes to society (return of information).

Let’s see how the participant-researcher vertices touch. Here, we must also be careful about the treatment and attention we have as researchers towards the participant, especially in qualitative design studies that put us in distinct places. In these, fieldwork involves being face to face with the participants in their community, and the roles can become confusing. Therefore, ethics in social sciences research must be considered a process because, by its nature, continuous questions and challenges appear in its deployment.

The same happens in the data-product relationship. For example, there are cases where researchers lie about the data found; they falsify the information, or there are interpretations with value judgments.

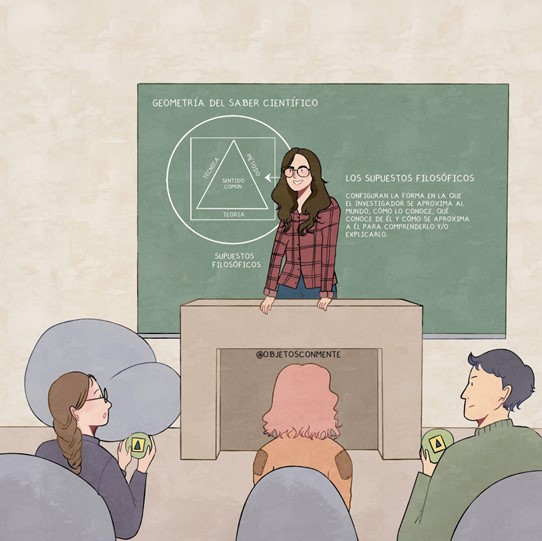

Image 3. Illustration of the geometry of scientific knowledge, Arreola (2020).

The circle

Finally, we have the circle, which surrounds the entire geometry of scientific knowledge. Here are the philosophical assumptions, thinking about ontology, epistemology, and axiology.

This part is often left aside during research formulation when it is forgotten to ask from where we know, how we know, and the relationship between who knows and how they know. These questions inevitably involve how we delineate the other decisions versed in the triangle and square.

The ontological assumption responds to how we think the world is ordered and its nature. We suppose a nature that follows a mathematical logic, one that responds to a single reality (positivist), or one that is subjective, multiple, and constructive (interpretative – constructive).

And from the epistemological assumption, we consider how we know, what we know, and from where we give to that other, we know; we consider these things as someone active within the research, who co-produces with us, or as someone passive, in addition to how we relate to those we know, and our values and ideologies (axiological assumption).

After doing a research project, one learns to predict and interpret facts with theories, reason with evidence and identify the various positions of the authors. You also learn to wonder about your position concerning a phenomenon. Learning about and learning in the social sciences is about understanding concepts and knowing how to interpret and explain them, which undeniably impacts our way of thinking and acting in the world (Pozo, 2016).

About the Author

Kathia Rebeca Arreola Rodríguez (kathiarreola@gmail.com; @objetosconmente) is an educational psychologist with a master’s degree focused on university students’ cognitive, affective, and learning processes. She designs and draws up pedagogical proposals to teach and learn science in Psychology. Her performance is concentrated in areas of teaching and research in both Mexico and Argentina. Her methodological approach to the development of research in education is qualitative, which led her to generate a learning space with students through the educational project @objetosconmente

References

Barton, P. (2015). Study participants and informed consent [American Psychological Association]. Recuperado de: https://www.apa.org/monitor/2015/09/ethics

Creswell, J. (2014). Research Design. Qualitative, Quantitative and Mixed Methods Approaches. SAGE Publications.

Epistemocentrismo, construcción del conocimiento científico. (Buenos Aires, Argentina). [Fundación Universitaria.] Obtenido el 12 de febrero de 2020 de https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZBwMcdd7Y4M&feature=emb_title

Geertz, C. (1975). Common Sense as a Cultural System. The Antioch Review, 33, (1), 5 – 26.

Glaser, B., & Strauss, A. (1967). Grounded Theory. Strategies for Qualitative Research. Aldine Transaction.

Limón, M., & Carretero, M. (1997). Las ideas previas de los alumnos ¿qué aporta este enfoque a la enseñanza de las ciencias? En Carretero, M (Eds.), Construir y enseñar las ciencias experimentales (pp. 349-384). Aique.

Penner, L., Dovodio, J., Piliavin, J., & Schroeder, D. (2005). Prosocial behavior. Multilevel perspectives, Annual Review of Psychology, 56, 365-392.

Pozo, J. (2016). Aprender en tiempos revueltos. Alianza Editorial.

Ravitch, S., & Mittenfelner, N. (2020). Qualitative Research. Bridging the Conceptual, Theoretical, and Methodological. SAGE Publications.

Rodríguez – Moneo. M., & Huertas, J. (2017). Motivación y cambio conceptual. Tarabiya; Revista de investigación e innovación educativa.

Rodríguez – Moneo, M., & Aparicio, J. (2004). Los estudios sobre el cambio conceptual y la enseñanza de las ciencias. Educación Química, 15(3).

Rodríguez – Moneo, M., & Aparicio, J. (2000). Los estudios sobre el cambio conceptual y las aportaciones de la Psicología del aprendizaje. Tarabiya: Revista de investigación e innovación educativa.

Samaja, J. (2007). La ciencia como proceso de investigación y dimensión de la cultura. Políticas científicas de la investigación en comunicación. Estrategias, sensaciones y diálogos sobre los estudios comunicacionales. 1 – 14.

Edited by Rubí Román (rubi.roman@tec.mx) – Observatory of the Institute for the Future of Education at Tec de Monterrey

Translation by Daniel Wetta.

This article from Observatory of the Institute for the Future of Education may be shared under the terms of the license CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

)

)

)