The re-education process needed to transform the way we communicate would generate essential tools for constructing inclusive classrooms and institutions.

Our societies are living structures that move and function through the diversity of those who comprise it: people. This diversity exists in our origins, nationality, gender, skin colors, sexuality, and opinions. Only the configuration of these axes’ reflective mechanisms opens up space to visualize our plurality as people in the world. One of these fundamental mechanisms is language.

Social relationships find their place of representation central in a system that shares their complexity and constant changes. Language may reflect positive cultural aspects like diversity and the discrimination and segregation still dormant in our spaces.

The guide for inclusive language prepared by the National System for the Integral Development of the Family (Mexico City, DIF, CDMX) explains that through our communication system, “we learn to name the world according to societal values […] and, depending on how language is used, can dignify, denote, or deny, generating prejudices, stigmas, and stereotypes.” So, resignification by a tool as powerful (and dangerous) as language “involves a transformation of social concepts and the widespread adoption of a culture of equal treatment.” This process arises from the validation of inclusive communication, but an approach to this much-needed alternative first requires identifying those uses of language that perpetuate harmful behaviors.

Is our way of speaking discriminatory?

As we mentioned, language is a structure that reflects the characteristics of those who use it; therefore, it is a living organism, subject to social, political, geographical, and generational contexts. Adapting to its speakers’ needs, language is adapted to the intentions of its speakers; consequently, it is also a tool applied in specific exercises of power still visible in our society.

When all persons are represented through a single part of the population’s appointment, the hierarchical figure and structure are validated. This concept permeates the way we decide to lead ourselves as people. If our society’s plurality is excluded from the foundations of our learning, then there is a problem. A challenge for gender-inclusive communication in English is the use of the masculine form by default. For example, “Every Permanent Representative must submit his credentials to Protocol,” explains the UN in its guide, Guidelines for gender-inclusive language in English.

The proposal to use language that legitimizes all the people who make up our spaces is uncomfortable because it questions structures that seem unquestionable. The truth is that this legitimization must be validated. Inclusive language is being used and introduced not only in social conversation but also in academia’s discourses. In our current society, social networks testify for transversal reform in our “sociopolitical, economic, and cultural paradigm,” as Andrea Lagneaux explains in her work, “Inclusive Language in the Classrooms: Problematization, Disputes, and Inclusion.” These changes also surface in how speakers decide to handle language.

Language as a political stance

Writings connect to society through the ideology that the author utilizes. They are constructions that express subjective ways of seeing the world, which possess particular socio-economic and cultural contexts. “Moreover, every context affects the realities, experiences of life, and social representations that the authors confront,” says Andrea Lagneaux. In this sense, language conveys power, and those who possess this power do not endure the inconvenience of being invisible.

The denial of the existence of this power “produces discourse that shapes reality from a single perspective […]”, as Silvia Castillo and Simona Mayo affirm in their article. Actively reformulating our discourse to advocate for minority representation is indisputably a political stance.

Let us clarify that language is not reality but represents and configures it. The goal of inclusive language is to consciously block harmful precepts that may infiltrate what the language communicates. “Its use identifies all people,” Castillo and Mayo stated.

Stigmatizing inclusive language

One of the stigmas related to the proposal for inclusivity is the impression of degraded language. This notion is based on the understanding that such reforms in the way we communicate violate languages’ beauty and nature. In this judgment, language is perceived as a rigid structure alien to sociocultural changes. However, applying restrictions contradicts the apparent flows that any language (understood as a phenomenon) must retain to remain practical and relevant to its context.

Language is a structure that reflects the characteristics of those who use it; therefore, it is a living organism, subject to social, political, geographical, and generational contexts.

Our language is connected and is inevitably “sensitive to extra-linguistic changes.” Attempting to communicate now using the Middle Ages’ speech would be quite problematic and even hindering. Through the phenomenon of language, we can visualize the social processes that have been the catalysts for reforms in its structure.

In addition to this conception, other questions arise from linguistic observations from a dissenting position. Understanding the function of language only as a communicative medium is not sufficient; one must question whether it possesses ideological tints on its own. Otherwise, the biases are not perceived as inherent in language, and it “is not conceived as a space for social rights disputes.” Here you would expect that once the reality is different, the context can change the meaning of the words without altering their structure.

However, the nature of language is not only a tool since it “creates thought, is thought when spoken, and, at the same time, represents and shapes reality. It is the central sense and medium by which we understand the world and build culture,” affirm Castillo and Mayo. Therefore, granting language a position very isolated from our social processes ends up fossilizing it.

The proposal for explicitly universal use of language is also questioned. As the Linguistic Society of America (LSA) explains, “some types of language commonly used in the past may now be considered offensive or exclusionary and may perpetuate stereotypes.” N

eutral language proposes to avoid “systematically using linguistic conventions that associate specific roles or professions with one gender in particular. This portrays certain individuals as having stereotypical qualities or associates them with membership in a particular community or social group having personal characteristics.” The questioning of this election sustains that there is confusion between “grammatical gender” and “gender as a social construct.”

Language conveys power, and those who possess this power do not endure the inconvenience of being invisible.

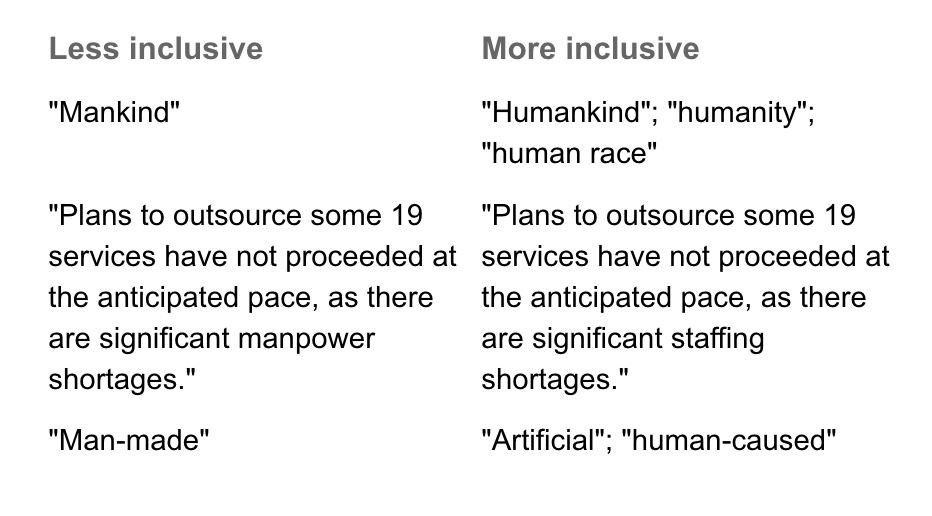

So, this argument maintains that the grammatical plane’s masculinized genre functions only to classify and has no connection with our social context (equally masculinized). However, both the system and its structure cannot be indifferent to the spaces where they operate. The LSA comments, “While it used to be assumed that there was an appropriate gender-neutral default term, research shows that a masculine pronoun or terms marked for masculine gender, such as man, are overwhelmingly interpreted as male even when users intend them to be understood more generally.” Also, this happens with terms that intend to be universal but perpetuate a masculinized view of the world: “It applies to terms like ‘mankind’ and ‘Congressman,’ as well; gender-neutral terms such as ‘humanity’ or “Member of Congress’ are preferable.”

“When speaking about ‘men,’ males are always certain to be included, as a male collective or as a representative universal human,” declares Lagneaux. From this ambiguity, Marquez Guerrero explains that “the human species is identified with all males and, as a result, the absence of women is naturally understood.” In this usage, it becomes irrelevant to mark the distinction of “men” with a generic or specific value because it becomes “the male in paradigm, the center, and measure of all things.”

The process of extending this faculty of the generic masculine to everything is gradual. Nevertheless, while it happens, minorities have the right to use resources that present them as visible within the language they use, even if these resources minimize their representation. This importance highlights the need for an economy of language.

It is equally transcendental to question the role institutions play as dictionaries and academies specializing in language, like Oxford and Cambridge and their equivalent in Spanish, the Royal Spanish Academy (RSA). Remember that only the people own the language; therefore, neither dictionaries nor academies govern or stipulate its use. Their job is to analyze changes in this system and usage choices that facilitate the communicative processes. Like any other institution, they can also take debatable positions.

“When speaking about ‘men,’ males are always certain to be included, as a male collective or as a representative universal human.”

Indeed, the path to equity between privileged positions and minorities will not be immediately shortened by specific changes in our way of speaking. Nevertheless, these changes contribute to the debate about systems needing reform, on a par with the changes that our society is experiencing.

A guide to inclusive language

Various institutional and governmental entities have joined the process to create projects that promote our language’s critical looks. In March 2019, for example, the Council of Europe adopted a report detailing specific recommendations to combat sexism. The document addresses how certain everyday practices perpetuate unsafe spaces for women, such as the production of biased social media content and advertising.

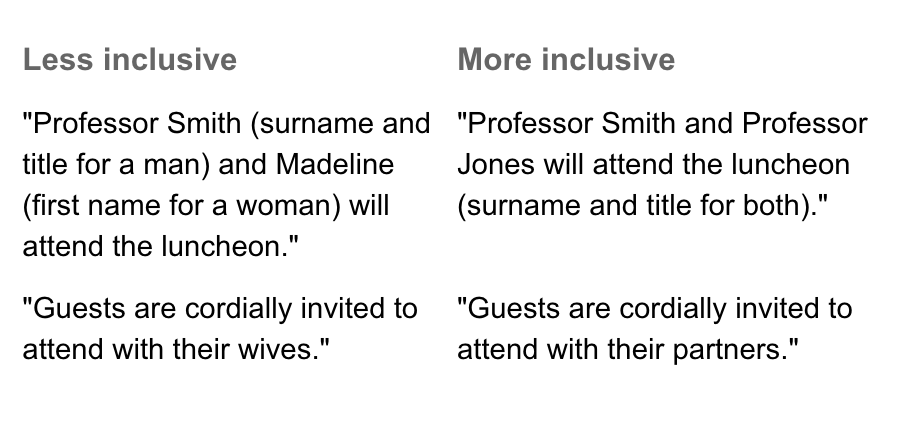

Similarly, the UN, in its publication, Guidelines for gender-inclusive language in English, offers crucial tools to accomplish transversal transformations in the way we communicate. Three key strategies for using inclusive language, and some examples for carrying them out, are mentioned:

1. Use non-discriminatory language

Discriminatory examples

“She throws/runs/fights like a girl.”

“In a manly way.”

“Oh, that’s women’s work.”

“Thank you to the ladies for making the room more beautiful.”

“Men just don’t understand.”

2. Make gender visible when it is relevant for communication

Using feminine and masculine pronouns

“When a staff member accepts an offer of employment, he or she must be able to assume that the offer is duly authorized. To qualify for payment of the mobility incentive, she or he must have five years’ prior continuous service on a fixed-term or continuing appointment.”

Using two different words

-

“Boys and girls should attend the first cooking class with their parents.”

-

“All of the soldiers, both men and women, responded negatively to question 5 in the survey.”

3. Do not make gender visible when it is not relevant for communication

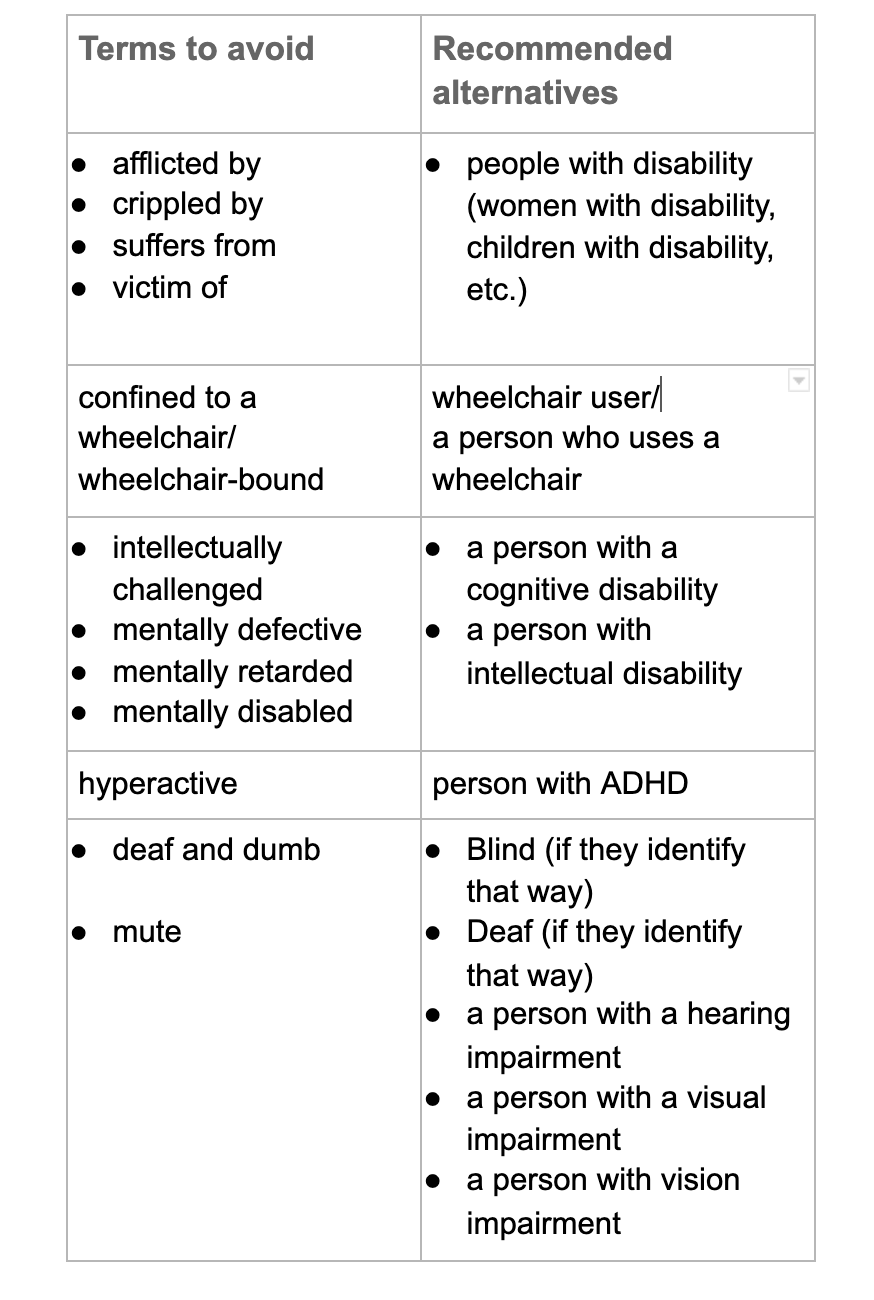

On the other hand, neurodivergent people and the community of persons with disabilities comprise an essential population of our societies. The International Labour Office (ILO) states that “an estimated 470 million of the world’s working-age people have some form of disability.” However, this plurality is not reflected in the way we tend to target these spaces. Discrimination against people with disabilities is reinforced by using pejorative terms such as crazy, retarded, and crippled. People With Disability Australia ORG recommends alternative descriptions for these harmful forms of expression:

What inclusive language means for education

For the norm in educational institutions to be challenged, transversal changes are required that cross the teaching system and curricula. This means integrating content to be equitable in the foundation of learning and eliminating subversive language.

This requires continuing re-education among the student body and the managers in “an effort to relearn how we address women and men in everyday life,” as written in the Non-sexist Communication Manual from the National Institute of Women. Students belonging to minorities, diverse ethnic-racial groups, and groups with different identities or opinions have the right to be represented in the language they use, even more so in a context where their representation is decisive for their comprehensive development of knowledge.

Teaching must raise essential questions about the normality of our understanding of the world. Even if the penalizations of punctuation in rigid academic contexts are still common practice, inclusive language development is not for debate. A language that makes the lack of inclusivity visible offers the right tools to make the student an active figure within this process, as uncomfortable as it may be.

Translation by Daniel Wetta.

This article from Observatory of the Institute for the Future of Education may be shared under the terms of the license CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

)

)

)