This morning, I was moved by the story of a young student unspeakably suffering because of the pandemic: Three of her close relatives died. Now she needs treatment to sustain herself emotionally, but her chances of receiving it are remote because she has scarce means at home.

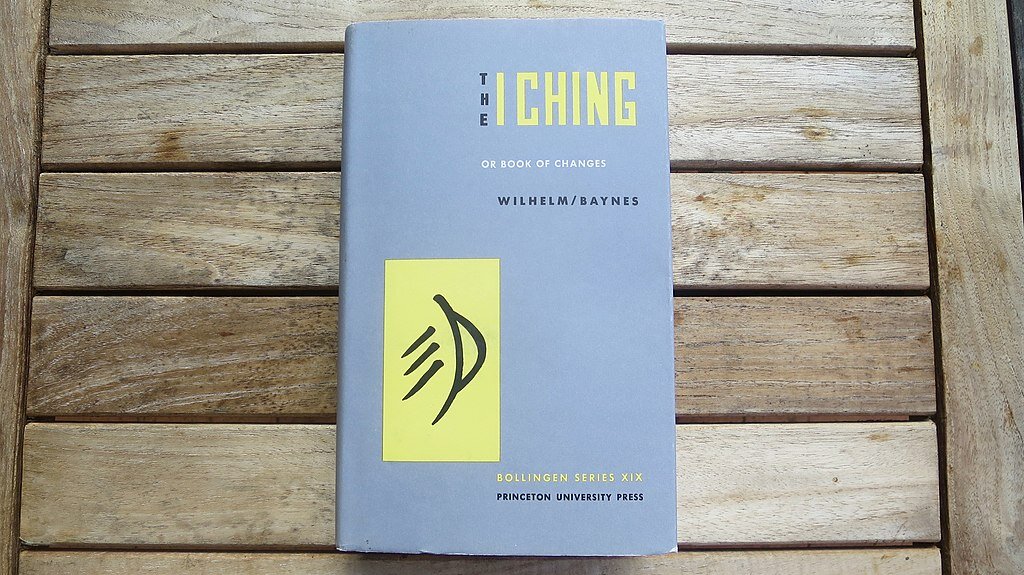

I immediately wanted to advise her teacher – my rapporteur – on how to support the girl. I remembered then some things that I reread last year in a book that has impacted me with its teachings throughout my life, the I Ching, a kind of oracular Bible of Taoist and Confucian doctrines, which combines the wisdom of many generations of teachers.

When the pandemic began, I looked in its pages for some guidance about what was starting to be experienced —hearing the story of the young student reminded me of this source. I discussed it with my rapporteur, and immediately after, I began researching how to share in this space some teachings from the I Ching on the best way to help others in an emergency.

Before turning to those pearls of wisdom from the text, I will allow myself to say a few words about a topic that floats in the air when one wants to provide support: I refer to the so-called goodwill. The reader will agree that well understood it deserves the utmost respect. The I Ching depicts goodwill as the gift that guides us on the right path. So does Immanuel Kant, by placing it somehow at the center of human moral behavior. Both sources speak of the purity of intention that we are all capable of living with philosophical rigor. However, as we already know, we all tend to sabotage our intentions as well. Helping is not easy; it compromises our inner and outer stability and puts us at risk. I think no one should feel guilty if they sense that they are unconsciously trying to make the process of helping someone fail. However, in times like the present, when pain somehow purifies our will, perhaps the knowledge offered by the great Chinese masters can serve us to persevere. As Kant says, “How magnificent is innocence! What a misfortune that it cannot be conserved and is so easily seduced! That is why wisdom, which consists more in doing (certain things) and leaving aside others, needs knowledge in order to last.” [i]

The I Ching comprises 64 major “chapters” that summarize the evolution of the cosmos, society, and each of us (according to the text itself). I especially turn to two of them, Kan, The Abysmal (number 29), and the so-called Chien, The Impediment (number 39). I intend to provide the reader with an agile consultation, so I extract only the core sentences from the original and summarize the rest.[ii]

*

In these times, the difficulties that our students experience do not seem extracurricular to anyone; they happen where they happen. However, once they come to us to tell us about them, we feel like skipping all the institutional protocols to run to help them. However, in those moments, we tend to forget something that the I Ching reminds us:

Any premature gesture can lead to failure.

Acting impulsively probably will lead us to commit basic mistakes. It could even seem like we want to impose our help. Indeed, we must always remain receptive to subtle signals required, but we must also be cautious not to push ourselves where we will not be well received.

However, making mistakes is not the worst thing that can happen to us. It would be sadder and more disappointing if our impulse to provide help were to be paralyzed or abandoned for not finding a viable path in front of us.

Sometimes, one is confronted with obstacles that cannot be overcome directly. In such a situation, it is wise to pause. This is preparation. One must join forces with companions and place oneself under the command of someone capable of facing the situation.

It is fundamental to begin by joining forces.

If one wants to count only on his efforts without the necessary precautions, he will not find support. He will perceive too late that he has made an erroneous calculation because the conditions he expected are insufficient.

However, preparing does not mean delaying help more than necessary. Once all forces are gathered, it is crucial to get down to work…

… move forward so as not to fail because of delay.

The truth is that we must do everything so that our willingness to help comes to fruition. It is not just a matter of personal whim; we must respond to a call that resonates within us and cannot be put aside.

… one is obliged to face danger for an important cause.

Once we are internally and externally ready to act, we must focus on the specific difficulty that requires our help. Our action should focus on immediate practical solutions in an emergency and not be distracted by addressing root causes (this is not the time to attempt major institutional, family, or personal changes).

It is not time to attempt significant transformations; it is enough to get out of danger.

Indeed, the emergency will deal us sufficient tasks because, at that moment, each student has different particular needs. We will have to understand them as well as possible and identify the resources we need for intervention. We will see that some are easy to attend (we will even run into students who urgently need to help others and who can become our allies). However, there will be cases involving various situations and people with whom it will be difficult to interact.

In her interpretation of the I Ching, the thinker Marta Ortiz compares the above to what Great Yu, a wise Chinese official, faced when he set out to control the flooding of the Hwang-ho River. For him, the strategy was to “honor the flow of water,” that is, to investigate and thoroughly understand what he was confronting and pay it the necessary respect.[iii]

In an emergency, it is not always easy to convince another that they need help or give it to them. This is not the time to rely on our eloquence; we have to offer proof. The same happens if we want to ask someone to collaborate with us.

If in difficult times one wants to enlighten someone, one must begin with what is evident.

In addition, having evidence will allow us to face the problem decisively and, very importantly, naturally, without too many preambles. Be proactive. This applies both to the people we want to help and to our collaborators and leaders.

(In times like these) conventional and far-fetched formalities are finished. Everything should be simplified to its essence. The main thing is a mental disposition to truth (and) the sincere intention for mutual help.

Therefore, we must trust our goodwill and act in a timely and respectfu

l manner, with sufficient knowledge and evidence. In most cases, our actions will achieve success. However, if we still cannot convince someone to get help, it is better not to continue. In any case, despite his indecision, we must trust that this person finds the right path (probably in a hectic way) and that he returns to us for support. In the parable on Youth Madness (number 4), the I Ching explains it thus:

It is not I who seeks the inexperienced young man; he must seek my help.

However, if after this the indecision is repeated, we will have to stop again.

When someone asks the same thing two or three times, it matters. If it matters, the information is not given to him.

*

The full text of the I Ching can be an excellent accompaniment for questions that arise along the way.[iv] I want to insist on always being practical and not deviating toward problems that do not represent the immediate need. I add a point that I consider crucial; it has to do with the last step of the process, ensuring that our effort comes to fruition and not letting ourselves wander at the last moment. In chapter 64 (Wei Chi, Before Consummation), the I Ching emphasizes that moment. It uses the metaphor of a journey that an inexperienced fox makes when crossing a melting river.

Nothing will be favorable if the little fox sinks its tail in the water when it has almost completed the crossing.

After overcoming challenging obstacles and already before the other shore, the animal can feel overconfident and misstep. Its abundant tail becomes immersed in the ice water, and its weight prevents the animal from moving forward. Everything can fall apart. Let us keep this in mind because a small effort in the last step can be crucial to achieve success and have the satisfaction of having done everything possible to help someone.

[i] Kant develops this and other ideas about goodwill in the book Foundations for a Metaphysics of Morals.

[ii] I take the following excerpts from Richard Wilhelm’s prestigious edition, both in its printed version published by Hermes Publishing House and its electronic version. (https://www.adivinario.com/download/I_Ching.pdf)

[iii] https://abatesoderini.blogspot.com/

[iv] Traditionally, the I Ching is consulted as an oracle; the interested reader can find the precise technique on the internet.

Translation by Daniel Wetta.

Disclaimer: The viewpoints expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the opinions, viewpoints, and official policies of Tecnológico de Monterrey.

This article from Observatory of the Institute for the Future of Education may be shared under the terms of the license CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

)

)

)