Juventino Jiménez, a visually impaired indigenous Ayuujk and teacher of the braille system, talks about the usefulness of the raised dots and how to use them in everyday life.

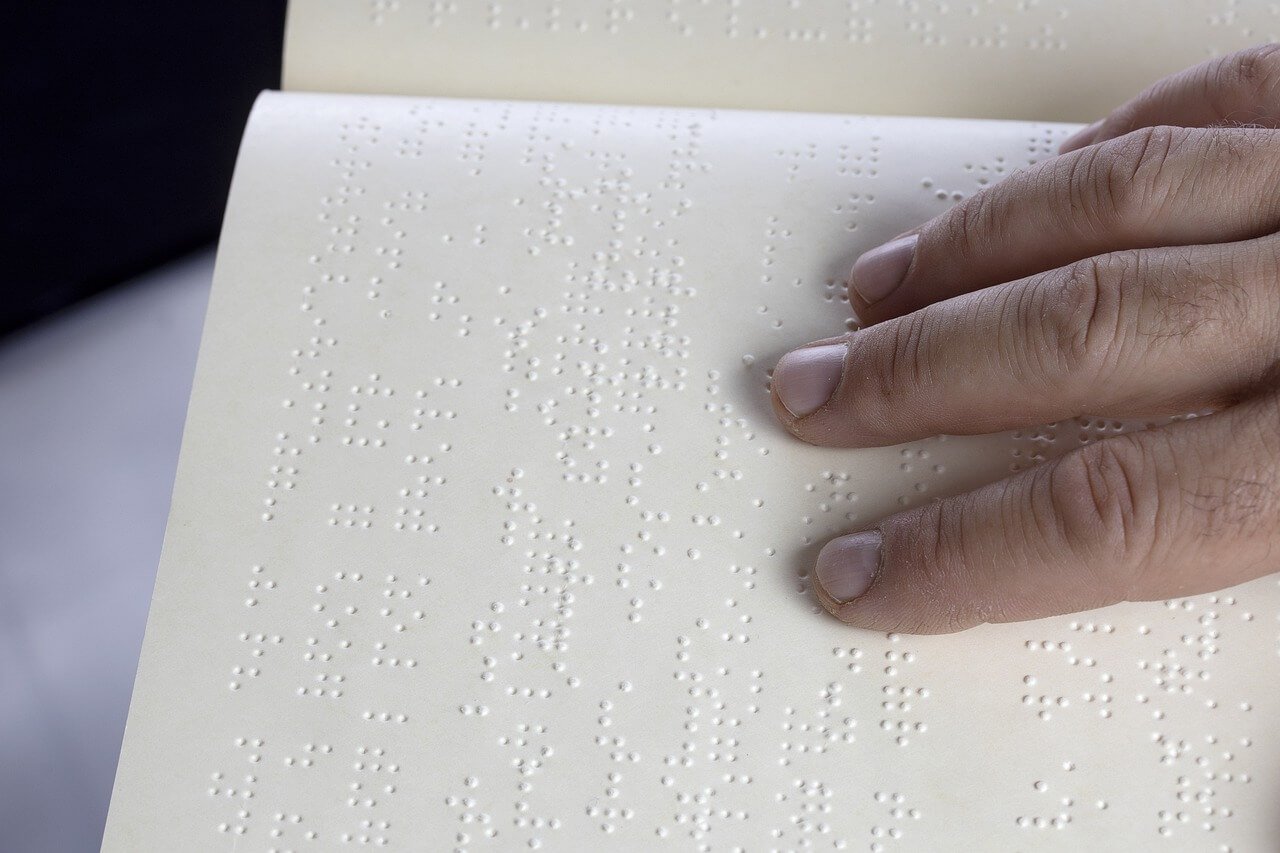

The sound of braille is the same as the pop that popcorn makes. People with normal vision write with paper and pencil, while blind people use cardstock, a slate (a kind of ruler with perforations), and a stylus (which looks like a sewing needle). They have to punch four or five dots in the paper to write each letter. Juventino Jiménez Martínez fell in love with that sound, the sound of the dots being punched on the page. He is a visually impaired indigenous Ayuujk, a teacher of this system, and an activist for indigenous rights and people with disabilities.

Juventino learned braille when he was 10. At that time, he had low vision, and using this tool was optional. “I liked how it sounded when someone wrote with it, and that’s why I wanted to learn it. Back then, I didn’t know I would go blind and that this would become one of my most beloved tools,” he says. This writing and reading system with raised dots is one of the few ways a person with visual impairment can know how words are written.

“The braille system is in the process of disappearing because children and young people aren’t learning it in inclusive education,” this teacher says. (Photo courtesy of the interviewee)

Like audiobooks

When Juventino began to learn this language, he only felt a universe of dots in his hands. He realized over time that reading in braille is a pleasure for him. “You can feel the construction of a letter, of a word in the tips of your fingers. You can feel each punctuation mark and know how a sentence is constructed,” he describes.

Juventino is also a teacher of this language. He says that young people no longer want to learn it because it’s enough for them to use software that reads the screens of their computers or cell phones. However, this system is the only tool that the blind or visually impaired have for learning spelling and the construction of written language. It’s as if a sighted person with normal vision only used audiobooks and had never read or seen a word. “Some say they’ve read a lot of books, but they’ve actually heard them. They can’t read; they don’t know the words,” he explains.

Technology can help

In Mexico, the use of this system has not been transferred to new technology. Only a few initiatives exist to adapt this language. For example, iOS has the option of a braille keyboard so that visually impaired people can type at the same speed as anyone else without needing to dictate. “It’s a wonderful tool in which you use six fingers. That makes it very fast. It’s free, and you write very accurately,” Juventino says. This is one of his strongest arguments for convincing young people to learn the dot language.

There is also a braille terminal device, which connects to computers, tablets, and cell phones and raises dots to display the words on the screen. However, they cost between 50,000 and 70,000 Mexican pesos. “Having a disability is expensive because you have to use additional tools to those used by a sighted person, such as a guide dog, software, etcetera,” says Juventino.

“We mustn’t allow Luis Braille’s legacy to disappear. We must rethink the way we continue to teach and use it in all areas of life.”

An ocean of books with only 200 titles in braille

For Juventino, there is nothing more pleasant than feeling every letter of the words that make up a story or a novel, but he realized there was a lack of books in braille when he was studying. He studied at the Primary School for Blind and Visually Impaired Children in Mexico City. Starting in middle school, he attended regular schools and remembers teachers asking him to read books, thinking that it was as simple as going to the library and asking for them.

According to Juventino, no more than 200 books exist in braille, and they are all literature, such as Don Quixote and some works by Gabriel García Márquez. There are only a few of them for three reasons: the cost of the printer, the paper, and the complexity of translating from ink to raised dots. A braille printer equivalent to an office or home printer costs 100,000 Mexican pesos. From there, the price goes up from half a million to one million pesos. The National Commission for Free Textbooks has Norwegian printers that cost millions of pesos. The paper they use is expensive because it is thicker than average. It needs to be 180-gram Bristol cardstock.

And finally, translation is difficult. “It’s not just about translating and sending them to print. You need to see how the format looks because, for every print page, there are on average three in braille,” he explains. Now there is a new method called interpoint. This allows printing on both sides, which saves half the space.

No academic texts exist for the blind

“Blind people don’t just read literature. We also need academic texts,” explains Juventino. In his bachelor’s and master’s programs, it was difficult for him to read at the same pace as his peers because he depended on screen-reading software that is not very accurate, let alone for sociology texts.

Sometimes, I had to listen to a sentence several times to understand its meaning entirely. “Our deficiency doesn’t limit us. Society’s barriers limit us,” he says. That’s why he co-founded the Letras Habladas (Spoken Literature) project at the Autonomous University of Mexico City and the Punto Seis (Point Six) association to create, print, and record academic titles that did not exist. Currently, they teach degrees in history, sociology, anthropology, political science, and health promotion for those who already have a collection of texts in braille or audiobook.

Don’t let braille die

From middle school on, Juventino has carried a slate, stylus, and cardstock with him. It was the way he could take important notes. Now he uses it to write down addresses and phone numbers on dangerous streets. “Nobody’s going to want to steal my slate, but they might want my cellphone,” he explains with a laugh.

He recommends that visually impaired people use this language to fend for themselves: “I write down my bank card numbers, my client number, and other important information, so I don’t need to ask for help when making a transaction or a call.”

This article from Observatory of the Institute for the Future of Education may be shared under the terms of the license CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

)

)

)