Academics, scientists, and organizations around the world have called for an end to the disproportionate legacy of European thought and culture in education and science.

During the 17th century, after the constant Western invasions of its territory, the indigenous peoples of the Amazon fell sick from a condition unknown at the time by their local doctors. Their ancestral treatments were not effective, and they had to resort to the science and hospitals of those who had introduced the disease.

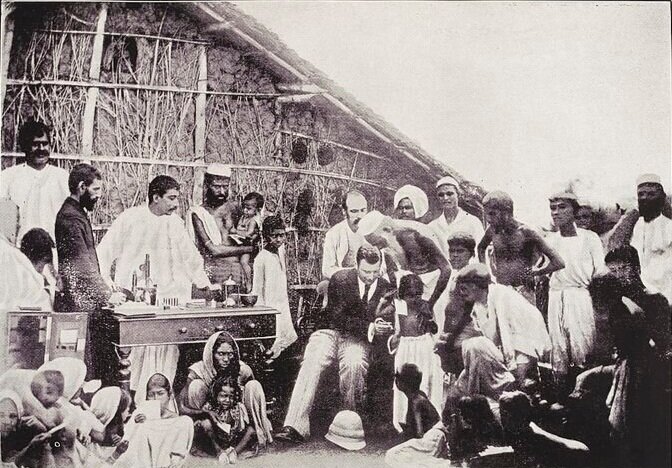

The actions of European empires to control the contagion in those communities led to the control of diets, routines, and movements of the inhabitants. David Arnold called this political process the “Colonization of the Body,” where Western medicine became a weapon to secure imperial dominance.

Under these circumstances, science was used to establish a definitive hierarchy in service to European power, where hegemonic thought was positioned as an absolute truth that ended up monopolizing knowledge. According to Jorge Molero-Mesa, professor at the Universitat Autonoma de Barcelona (UAB), the strategy behind the “infallibility” of this knowledge lay in the contempt and constant discrediting of indigenous methods. This discourse differed from other mechanisms of colonization, since, unlike religious, social, and economic concepts, medicine did not allow any discussion of its universal validity.

From an imperialist point of view, the indigenous people, ignorant of Western methodologies, lived in a significant “secular backwardness;” therefore, the Western powers depicted the colonizing process as morally justified. Sophie Bessis explains it as follows: “The paradox of Western science lies in its ability to produce universals, elevate them to the rank of the absolute, violate the principles that derive from them with a fascinating systematic spirit, and then elaborate the theoretical justifications of these violations.”

The epistemological subordination generated, sought to lengthen the scientific and technological dependence of the colonized countries for as long as possible. They viewed their knowledge as a divine gift. To the European authorities, colonization meant “the end of barbarism and the beginning of civilization,” thus relegating native medicine to a secondary role in the development of scientific research.

European scientific success in this period was based on the sacking of colonized peoples, as the same violent processes that gave imperialism its power were used to generate the scientific knowledge of the age. “Modern science was effectively built on a system that exploited millions of people. At the same time, it helped justify and sustain that exploitation, in ways that hugely influenced how Europeans saw other races and countries,” comments Rohan Deb Roy to Smithsonian Magazine.

Western medicine is considered one of the most powerful and penetrating tools of the entire colonization process, an enduring legacy that still prevails in the trends of current science.

“Colonial Science” or “Parachute Science” in modern academia

Asha de Vos, the founder of Oceanswell, Sri Lanka’s first research and educational organization for marine conservation, explains the term “parachute science” for Scientific American as “the conservation model where researchers from the developed world come to countries like mine, do research and leave without any investment in human capacity or infrastructure. It creates a dependency on external expertise and cripples local conservation efforts. The work is driven by the outsiders’ assumptions, motives, and personal needs, leading to an unfavorable power imbalance between those from outside and those on the ground.”

This method implies that various powerful educational institutions and private corporations benefit from the research and work of academic bodies that are under financial and disciplinary dependency to their native countries. The result is that their experiences and discoveries receive priority.

“Modern science was effectively built on a system that exploited millions of people.”

In recent times, various calls have been issued to “decolonize science.” The journal Nature defines these as a movement to eliminate, or at least mitigate, the disproportionate legacy of European thought and culture in education. The main objective is the equitable generation of research sources along with continuing investments in local scientific talent and infrastructure.

The footprint of the scientific hierarchy can still be observed in various scenarios. Most journals, academic research, and ranking organizations belong to institutions in the United States and Western Europe. “Scientific collaboration between countries can be a fruitful way of sharing skills and knowledge and learning from the intellectual insights of one another. But when an economically weaker part of the world collaborates almost exclusively with powerful scientific partners, it can take the form of dependence, if not subordination,” says Deb Roy.

A study by the Hungarian Academy of Sciences conducted in 2003 analyzed peer-reviewed publications, encompassing more than 7000 journals in all the sciences. The study found that the research that had been held in the least developed countries did not show co-authorship with the local research institutes in 70% of the cases and that research institutes published most of the papers in the most industrialized countries of the world.

The same study examined the possible causes of this tendency, looking at the opinions of the authors in the studies. Many of them defined the tactics used by researchers from developed countries: They endorse the importance of recognizing contributions to research, but they deliberately and systematically exclude co-authorship of researchers in smaller institutions as a form of scientific neocolonialism. It was also found in most of the studies that local scientists were much more inclined to do fieldwork in their native country for foreign researchers.

Equally, the sparse representation and discrimination against researchers belonging to ethnic minorities (even more so if they are women) stand as stark evidence about the obstacles that science still holds for all those who are not part of the Western scientific prototype.

The Pew Research Center found that people of racialized ethnicit

ies working in STEM are four times more likely than Caucasian people to say that their workplace does not put sufficient effort into increasing racial and ethnic diversity. About half of them mention that they have experienced employment discrimination, and “approximately one in eight (12%) in this group say they have faced specific barriers in hiring, promotions, and salaries in the form of lower wages or fewer promotional opportunities than their white work associates.”

“The workplace is still geared to the promotion of whites over minorities regardless of the laws in place to promote equality in the workforce,” explains one of the survey respondents. In cases where systemic racial subordination combines with sexism, the scenario becomes even more discouraging. UNESCO affirms that in the Sub-Sahara, only 30% of researchers in all branches are women. Many of those found in STEM fields tend to abandon their careers in academia in their second year because the system was not created nor has been adapted for their protection and academic encouragement. Moreover, for those who are already working professionally, their responsibilities, and the power to make decisions are very minimized.

Asha de Vos also explains how in areas of environmental conservation, research in foreign countries was affected after the confinements of the coronavirus began. Many of the researchers who had not tended to the ongoing training of local partners for fieldwork had to face a data hole in the scientific compilations that they had been working on for years.

As the borders remain closed and the world is practically in isolation, Asha points out that “this period highlights the need for strong, on-the-ground partnerships if we are to succeed in our conservation efforts.”

Steps in the process of scientific decolonization

Rohan Deb Roy suggests that the institutions, organizations, and museums that have imperial collections should be encouraged to reflect upon the violent political processes in which these objects of global knowledge were acquired. The goal would be to provide research that is much more ethical and democratic.

“To decolonize and not just diversify resumes is to recognize that knowledge is inevitably marked by power relations.”

Along these lines, the scientific collaborations discussed above must undergo transversal changes in the methods of recognizing co-authorship and scientific research outside the hegemonic world. Starting the conversation about the constraints that the non-Western academia has had to suffer would also lead to a significant change in their participation in scientific creations.

The dissemination of learning from equitable sources is crucial for the reflection and conscious collective memory about the not-always-ethical path that scientific discovery has traveled throughout history. Students must have the opportunity to learn about the role that Western medicine played in the colonizing process and in the creation of racial and sexist prejudices that continue to persist in the modern world. Deb Roy also states that a reconstruction of knowledge dominated by the European white man is necessary and, even more, that this history of decolonization in the development of science reaches the schools.

Cambridge University professor Priyamvada Gopal states that “to decolonize and not just diversify resumes is to recognize that knowledge is inevitably marked by power relations. A decolonized resume would bring questions of class, caste, race, gender, ability, and sexuality into dialogue with each other, instead of pretending that there is some kind of generic identity we all share.” She also notes that those minorities not accustomed to being reflected in the scientific development of the modern world “have as much right as elite white men to understand what their own role has been in forging artistic and intellectual achievements.”

Although most of the universities that have decided to take action on this issue have started by increasing the number of researchers coming from these groups, various sources assert that now the evolution of uniquely Western knowledge should highlight the historical contributions of marginalized communities in history and confront certain unpleasant aspects of history in science.

The call for the elimination of parachute science is much more complex than just increasing the number of minority research authors in scientific papers (although necessary). Primarily, it involves transforming the way conventional textbooks are read and asking uncomfortable questions about the scientific processes that took place in previous centuries. “Decolonization is going to happen in the mind,” says Siyanda Makaula.

Translation by Daniel Wetta.

This article from Observatory of the Institute for the Future of Education may be shared under the terms of the license CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

)

)

)