A Stanford University study has identified four consequences of Zoom fatigue and raises changes that people can easily implement to avoid it.

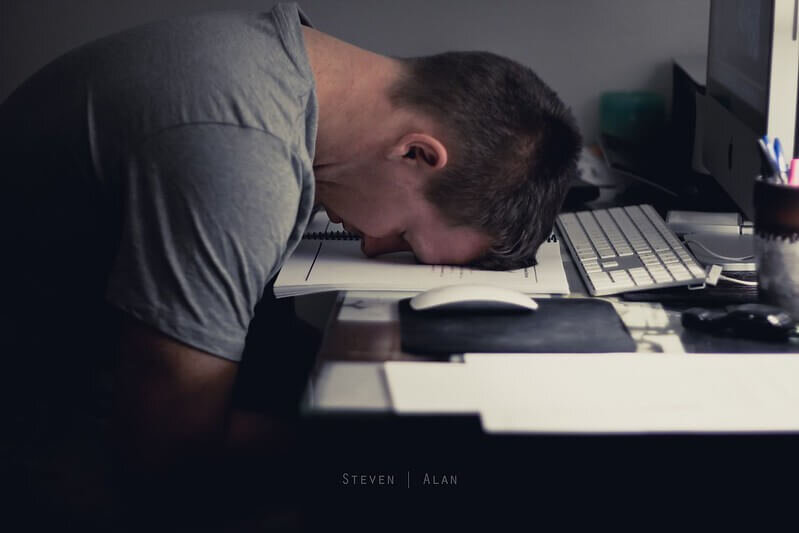

The term burnout may sound familiar to students or “high-performance” professionals. Because of the great demand for social distancing caused by the pandemic, thousands of institutions have been forced to replace their face-to-face classes with virtual video sessions supported by digital platforms. Students, professionals, or teachers currently spend many hours in front of a screen to perform their daily school or workday tasks. The widespread telework and “Zoom schools” are products of the pandemic that result in these endless hours of watching a screen. It is wreaking havoc on people, giving way to a phenomenon known as Zoom-fatigue or Zoom fatigue, which comes from the long hours on the computer in virtual meetings. It was given this name because of the popularity of the Zoom platform. However, a Stanford University study confirms that Zoom fatigue is only a reference to the boom that this platform has seen recently. This fatigue can result from excessive exposure to any video conferencing platform.

Professor Jeremy Bailenson, the founder of Stanford’s Virtual Human Interaction Laboratory, examined the psychological consequences of spending so many hours on these platforms. In the paper published in the journal Technology, Mind and Behavior in February this year, the professor identified four consequences that can cause Zoom fatigue. He states that his purpose is not to discourage using video conferencing platforms; even he uses them frequently. However, he points out minor problems presented by these programs and suggests some changes that users can easily implement to avoid this fatigue.

Zoom Fatigue: Four Problems and Solutions

Problem: Excessive visual contact is highly intense.

Bailenson begins by highlighting that the amount of eye contact we have in video conferencing is unnatural. In a face-to-face conference, the rhythm of our gaze would be very different because we glance at our notes, the person talking, the screen, the clock, and other things. So, face-to-face conferences or meetings are often less exhausting, but during virtual conferences, our gaze remains all the time on the members we see on the screen. Dr. Bailenson says, “a listener is treated just like a speaker,” and the level of eye contact increases dramatically. Bailenson compares it to social anxiety, where one of the most prevalent phobias of people, the fear of public speaking and knowing that all eyes are on you, is a high-stress experience.

Another source of stress is the window size displaying to the person, which depends on each person’s monitor. Faces in video conferencing tend to appear much bigger than they are, which can become uncomfortable. When a physical conversation between two people is simulated, the other person is seen at a size natural in the desired personal space. When you see a person on a large screen, you perceive their size and space much more intimately. Finally, when a person is a short distance from us, our brains interpret it as an intense situation that will lead to mating or conflict.

Solution: The recommendation is to avoid full-screen mode, thereby reducing people’s screen size, and use a monitor-independent keyboard to create more space between yourself and the screen.

Problem: Admiring yourself during conferences is highly exhausting.

Admiring oneself in real-time is an unnatural experience. Bailenson compares it to the situation of having someone following you with a mirror all the time while you talk, argue, make decisions, give or receive feedback; it would be something no one would choose to experience. Similarly, some studies show that when you are in the presence of your reflection, you become more critical of yourself, and seeing ourselves in video conferences hourly is having its repercussions on us. Also, many studies prove that seeing your reflection for a long time has negative emotional consequences.

Solution: The teacher proposes that the platforms disable the self-image function during the session, saying that the view only needs to be outward. Alternatively, you can disable the camera function to achieve the same effect if the class professor allows it.

Problem: Habitual reduced mobility.

Face-to-face meetings gave people more opportunities to move and walk around. Still, in video conferences, the cameras have only a single angle, so the person is forced to stay within a contained area with little space. The person’s movement is limited in ways that are not natural. Bailenson points out that recent research indicates that people have better cognitive results when moving.

Solution: Be aware of the space where you work and attend video conferences and how the camera is positioned. Add additional elements such as a mouse or keyboard to create flexibility.

Problem: Increased cognitive load

Nonverbal communication is much more frequent in personal encounters, but on video conferencing platforms, this is eliminated. In non-verbal communication, each person naturally interprets the gestures or signals subconsciously. In video conferences, we have to work a little harder to send these signals or receive them. Bailenson describes how we have transformed something natural for humans, conversations, into something that requires much mental effort. Nonverbal language lightens conversations a lot because it can reduce our words to a simple glance or gesture. However, when we try to translate our communication into the virtual context, it can mean something completely different.

Solution: In the middle of long meetings, take breaks by turning off the camera and only using audio. In this way, we stop being verbally active for a few moments and let our minds take a break. The body also rests for a while from the screen.

Similarly, the BBC published an article in April last year, at the peak of video-call conversations. They compared many of the social situations that have been compromised by this new system and how they have been unconsciously affecting us. When we would generally consider a call with our friends relaxing, Professor Marissa Shuffler of Clemson University realized that long calls could feel merely performative. It is like watching TV, and TV is watching you. She also mentions that it does not matter if we call it a meeting with friends; when the same tool is used for work, there is a high probability that it will affect us like an activity we do not want to do voluntarily.

Some of the solutions that Professor Shuffler proposes are limiting video conferencing to only those that are strictly necessary, taking breaks where the camera is turned off, or only choosing to use the audio. Move camera positioning to the side or where you cannot see it to maintain concentration, especially during large group calls. Do a check-in at the start of conferences to know everyone’s well-being before delving into the session’s topic. It is a way to reconnect ourselves with the world and regain confidence and reduce fatigue and worry.

With all this, we can realize that, definitively, our bodies are not designed to spend long hours observing a screen in a single position. It makes us miss even more the in-person coexistence. However, we should not give up because the human being is good at adapting. Both Bailenson and Shuffler have given us keys to correct little things that consume our energy and advice to take full advantage of our work, education or proposals. Thus, we can continue going forward, adapting to the current situation that we are experiencing.

Translation by Daniel Wetta.

This article from Observatory of the Institute for the Future of Education may be shared under the terms of the license CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

)

)

)