The United States is no longer the “undisputed leader” in science worldwide. China is advancing in leaps and bounds at international university rankings.

China is advancing in leaps and bounds at international university rankings stepping on global veterans’ heels in the Top 10, including Oxford, Harvard, and Stanford. Historically, the United States has dominated the world rankings in the sciences and research, yet its hold on these positions continues to weaken.

According to the latest edition of THE World University Rankings, China is the first Asian country to reach the Top 20 in the rankings since Times Higher Education changed the methodology in 2011. That position was earned by Tsinghua University, which climbed three places to rank number 20 this year. The Asian country has also doubled the number of institutions in the top 100 from three to six. Most of its top 20 universities maintained or improved their performance over previous years.

American Universities in Decline

In contrast, the performance of American universities is in decline. Although the United States still dominates the top of the rankings, the number one position was taken by the University of Oxford (United Kingdom) for the fifth consecutive year. On the other hand, half of the top 20 U. S. universities dropped this year. None of the U. S. universities ranked between 201 and 300 in 2016 reached the top 100, and some even dropped several places since then.

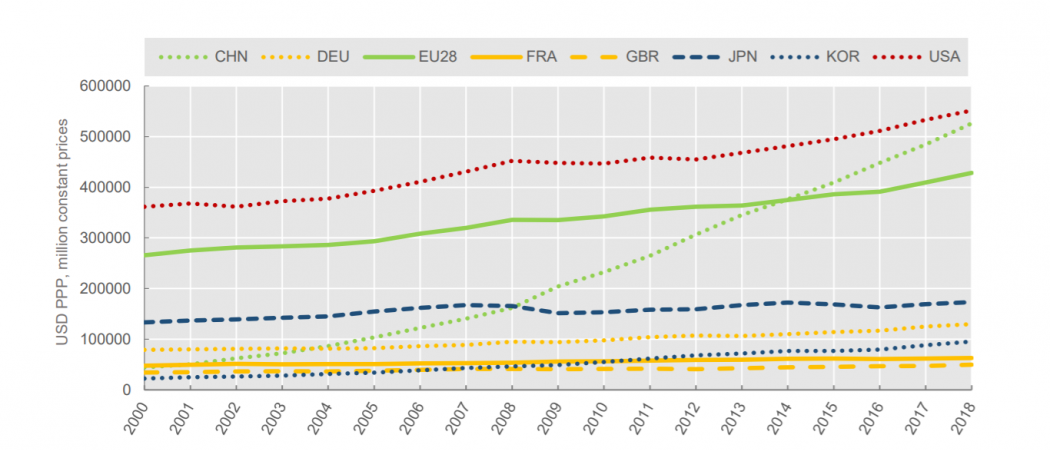

Experts project that China will surpass the U.S. by 2022 as the number one nation investing in research and development (R&D).

While the dominance of the United States’ universities seems to have been declining steadily for some years, Chinese universities have been moving forward at a steady clip. Experts on the subject predict that the pandemic may further accelerate the growth of China. The Coronavirus crisis has put the U.S. higher education sector in a “critical financial position.” Why? It is partly due to the austerity measures implemented in the wake of the pandemic and the so-called “disaster capitalism,” where companies, institutions, and government entities reduce spending and investment during a natural disaster or crisis like the one we are experiencing. “The reduction of university income and expenses and the dismissal of teachers and temporary research staff affect research productivity and institutional reputation, which are fundamental in the world university rankings,” points out Wei Zhang, a professor at the University of Leicester, in her comments to Times Higher Education.

But how did we get here? What is the key to China’s advance in the world rankings?

Keys to Chinese success: Long-term vision and investment

The country’s achievements in the 2021 edition of the Times Higher Education ranking derive from a long-term steady advance strategy that began more than a decade ago. Large amounts of money invested in science and research sustained this vision of the future. Over the past decade, China has become a power in science and technology. Its progress is even more impressive than the stories propagated about South Korea and Singapore’s success.

To achieve this success, the Chinese government has spent money (a lot) to attract and prepare talent, send students to the best universities in the world, bring them back, and offer permanent positions to both nationals and foreigners in their research centers and universities.

Gross domestic expenditure on R&D, 2000-2018. Source: Science | Business.

The United States is no longer the “undisputed leader” in science worldwide, says the National Science Foundation. Chinese universities have been closing the gap with the United States regarding the impact of citations since 2018. This year, the quality of research from Chinese universities in the middle range even outperformed their USA peers. Moreover, for the first time in history, China’s median research income was higher than that of the United States in this year’s report. Taking this trend into account, the U.K. Research and Innovation Agency projects that China will surpass the United States in 2022 as the number one nation in R&D investment.

Our Country has lost, stupidly, Trillions of Dollars with China over many years. They have stolen our Intellectual Property at a rate of Hundreds of Billions of Dollars a year, & they want to continue. I won’t let that happen! We don’t need China and, frankly, would be far….

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) August 23, 2019

However, the success and growth of the Asian country have not come without criticism of its approach and strategy, arguing that Chinese scientific production is of low quality and dubious ethics. Complaints mainly focus on intellectual property protection, about which the United States has been quite vocal (Trump, in particular). “They have stolen our intellectual property at a rate of hundreds of billions of dollars a year and want to continue. I will not let that happen!” he tweeted in August last year. The fight over intellectual property has led to high tension between the two countries.

However, what Trump forgot to mention is that the scientific research conducted in the United States is supported by foreign scientists, mainly from China. According to Nature, close to 40% of scientific articles published by U.S. authors in 2018 included foreign co-authors, up from 19% in 2000. The Chinese scientists contributed to more than a quarter of these papers. More than seeing China as an adversary, the United States should consider it as a great contributor.

Criticism of the Chinese universities’ incentive system

However, the alleged “theft” of intellectual property is not the only aspect of Chinese science subject to criticism. The quality of made in China science has also fallen into stereotypes. While the Chinese universities’ “money-for-articles” incentives have mostly had a good response (Chinese scientists can earn bonuses up to 165,000 dollars for being published in the international scientific journals), some academicians actively resist this, arguing that such schemes tend to reward quantity over the quality of research.

They are not entirely wrong. This highly-incentivized strategy to publish and the lamentable slogan “publish or perish” have resulted in the proliferation of “paper mills.” This refers to researchers, under constant pressure to publish, hiring external agencies (freelancers) to write papers quickly; as some point out, these often have false data and results sent to scientific journals. China has been involved in some prominent cases of suspected peer-review fraud. In April 2017, the journal Tumor Biology retracted more than 100 Chinese authors’ articles after publishers found “strong reasons to believe that the peer-review process was compromised.” According to an analysis by Simon Baker, this type of fraud occurs when the email addresses of peer reviewers suggested by the authors turn out to be controlled by themselves or companies connected to them.

In the face of criticism, China is already taking up the issue. On the one hand, the Chinese government has announced that it will distance itself from the “publish or perish” culture to assess these problems and minimize the impact of the metrics used to evaluate academicians and universities, expressly the Science Citation Index (SCI). This trend is not unique to the Asian country.

In March, Joyce Lau y Jing Liu reported that this measure, jointly issued by China’s Ministry of Education and the Ministry of Science and Technology, seeks to discourage universities from rewarding researchers and departments based primarily on the number of published articles they have in the SCI, a database owned by Clarivate Analytics. The SCI is one of the world’s leading bibliometric indices for research.

The Chinese government has also taken steps to prevent plagiarism and data falsification in its publications. China’s Ministry of Science has announced a series of measures that will come into force this month and apply to anyone involved in purchasing and selling academic items or data fabrication.

This is how China is reassessing the aggressive strategy it began taking a decade ago to advance in the world rankings. According to Times Higher Education information, the Chinese government has published a document discussing the problem of “SCI supremacy.” This position paper makes public China’s dissatisfaction with the current research system that relies predominantly on the SCI when decisions are made about available positions, hiring, and funding.

However, China is not the only country reflecting on the current research system that affects scientific production worldwide, researchers, academicians, and professors’ physical and mental health.

To counteract the widespread attitude of “publish or perish,” the British Science Association’s former president suggested a radical proposal to combat this problem last year: restrict researchers to a single academic paper per year. Uta Frith, a professor emeritus of Cognitive Development at UCL, advocates a “slow science” that counteracts the relentless pressure to publish. For her part, Dutch Minister of Education Ingrid van Engelshoven notes that academicians should not work on weekends and holidays. Professional competency in academia has gone “too far,” warns the Minister, who also stated that her country would take steps to reduce stress and pressure in the sector. Hopefully, more countries will follow this example and start moving away from academia’s toxic culture towards a “slow science” revolution.

Translation by Daniel Wetta.

This article from Observatory of the Institute for the Future of Education may be shared under the terms of the license CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

)

)

)