One in four SNI-member researchers associated with private universities has been left out of CONACYT’s support system.

Recently, the press has reported on diversion of funds in CONACYT, the disappearance of trusts set up for science and research, and the federal government’s decision to withdraw financial support to researchers and professors at Tecnologico de Monterrey. The latter has generated serious protests by teachers and academicians affiliated with the private Mexican institution.

The lack of resources for research and development and their mismanagement at the national and global level are very grave matters. However, it is crucial to have a broad understanding of the issue to know precisely what is happening and how. Understanding this, we can start a conversation that leads to real solutions for problems involving research and development tools. We need to know first about the ones principally affected, the members of the National System of Researchers (SNI).

What is the National System of Researchers, and how does it work?

The National System of Researchers (SNI) was created by a Presidential Agreement published in the Official Journal of the Federation in 1984 to recognize the work of people dedicated to producing scientific knowledge and technology. The SNI’s objective is to promote and strengthen the quality of innovation and national scientific and technological research in Mexico. They achieve this through peer evaluation within their scientific community.

Similar organizations exist around the world. The United States has the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS), and the United Kingdom has The Royal Society. Chile is home to several agencies of this kind, such as the Chilean Society of Physics and the Chilean Society of Scientific Education. Organizations that promote and stimulate scientific work are a basic need for the continuity of education and development in all countries. Hence, there are government agencies whose purpose is to incentivize, finance, and enable scientific work.

Evolution of science and technology public spending (as GDP percentage and total public spending percentage).

In Mexico, this is done through the National Council of Science and Technology (CONACYT); its work is stipulated in the General Education Act. According to Article 25, the State must invest at least 8% of GDP in Education, of which 1% should be directed to scientific research and technological development conducted by public higher education institutions. CONACYT, in theory, administrates and distributes funds for the production of scientific knowledge.

However, this goal has not been achieved in more than a decade. Investment in knowledge suffers from a national deficit that disadvantages it, especially compared to the resources allocated to scientific communities in other countries.

How does investment in knowledge operate at a worldwide level?

The federal investment in science and technology has not been consistent in reaching the 1% stipulated in the General Education Act in more than a decade. Invested funds ranged from 0.2% to 0.3% of GDP before 2014. There was an uptick between 2014 and 2015, with the figure rising to 1.5%. Subsequently, there was a marked decrease in the approved budget in 2019. The budget presented for academic and scientific production for 2020 only amounted to 0.8% of the federal budget (0.4% of GDP). This amount translates to 49.4 billion pesos.

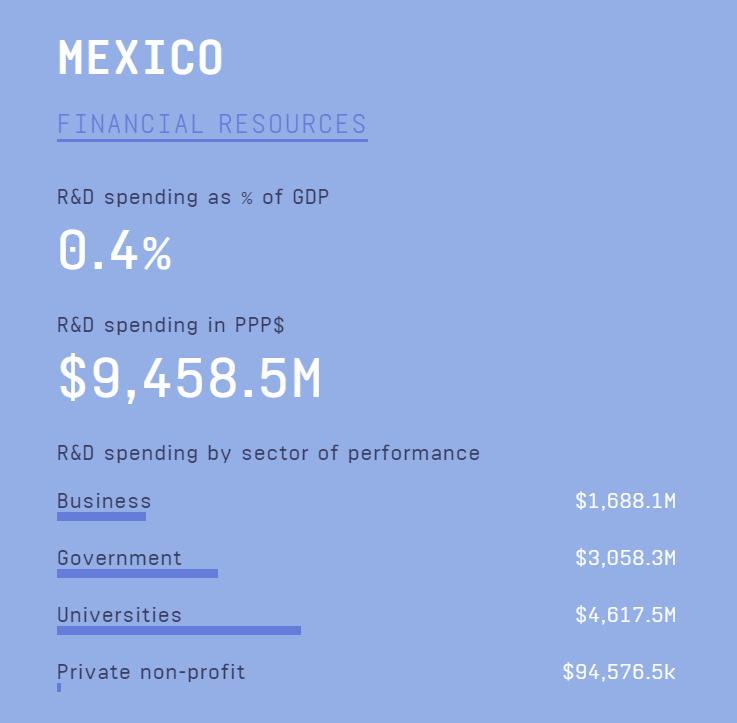

A broader idea of how investment in knowledge, research, and development is handled globally can be seen in the UNESCO statistics. Measured in Purchasing Power Parity Dollars (PPD) for better validity and transparency, the UNESCO data indicate how much of its GDP each country invests in research and development and how much this would be in monetary terms.

This is crucial for discerning the significance of resource management and the scientific advances these assets make in each country. GDP is not enough to know how much a country invests in its scientific community. For example, Japan, which holds the first place in the percentage of GDP invested, spends 3.4%, which equates to 169.6 billion PPD dollars. The United States invests only 2.7% of GDP, but this translates to 476.5 billion PPD dollars.

How much does Mexico invest, and why did the federal government consider it necessary to reformulate the way research and development resources are managed? According to the UNESCO data, Mexico invests 0.4% of its GDP, amounting to 9.5 billion PPD dollars.

The breakdown of the managers of this investment nationally is as follows: In first place are the universities, which contribute $4.6 billion PPD, closely followed by the government with $3.06 billion; third, the private business sector invests $1.7 billion, and the private non-profit sector collaborates with $94.6 million. According to the numbers, both the higher education institutions and the federal government have been the greatest benefactors of knowledge and science production. However, if this is the case, why are we entering the historical moment in which they do not behave like allies?

Politics and corruption in the distribution of incentives

The federal government’s categorical and quick steps to tackle corruption in distributing funds for scientific production have generated widespread concerns and significant protests, especially in the private higher education sector. Institutions affected by the withdrawal of support include Tecnológico de Monterrey, the Iberoamerican University, and Instituto Tecnológico Autonomo de Mexico (ITAM)

Why is the federal government making these decisions? These actions intend to respond directly to rampant corruption where massive diversions direct funds and resources to private companies instead of the scientific community.

The Newspaper El Horizonte reported this past 22nd of October that the federal government alleged that CONACYT awarded million-dollar sums to private companies. According to government information, CONACYT unjustifiably handed over 15 billion pesos to private companies between 2013 and 2018. On this basis, the federal government acted to stop the diversion of resources, but this is not the real issue here. It is not disputed that corruption in resource-sharing mechanisms required a response from the federal government.

However, the elimination of 109 trusts recently sanctioned by the Senate came as a heavy blow. There was no preliminary analysis to support this course of action, no communication strategy, and no alternative proposal that would calm the concerns of educational institutions, the scientific community, and the general public regarding a new way of distributing resources. This bungled process has resulted in one of four SNI private university researchers being left out of a support network. This represents 23.8% of the community dedicated to research and development nationally.

Considering that the universities invest the most capital for research and development in Mexico, the government’s decision to break the agreements with private universities, arguing that it aims to cut off the diversion of resources to businesses, appears to be more performative than efficient. The consequences of this action can be disastrous for the development of Mexican science.

If this protocol persists, the withdrawal of support could affect 50 universities, potentially leaving the national production of scientific knowledge without an engine. The government’s executive and legislative branches must develop and present a clear strategy for the administration and distribution of resources to protect assets for epistemic and scientific production, without cutting ties or agreements with the private higher education institutions.

Translation by Daniel Wetta.

Update: In the original version, published november 3, 2020, it was said that one of every four SNI researches were out of the Mexican federal support network. A more accurate fact shows that this proportional number covers only SNI researchers with positions in private universities.

This article from Observatory of the Institute for the Future of Education may be shared under the terms of the license CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

)

)

)