To reflect students’ progress in the acquisition of competencies in the science laboratory, we designed an analytical rubric to define what is expected of the student. With this same rubric we can give assertive feedback about their performance in a personalized way.

Photo: Bigstock

The aim of a competency-based educational model is to integrate knowledge with the development of the skills, attitudes and values that comprise a competency. The key question we need to ask ourselves as teachers is, how can we ensure that students will acquire the competencies defined for a specific course? The first step in answering this question is to find a congruent line between the activities students carry out in class and the way in which they are being evaluated. A common mistake when first using a competency-based model is the gap that exists between what we expect students to learn and the force of habit to evaluate them in the traditional manner with exams and quizzes.

“A common mistake when first using a competency-based model is the gap that exists between what we expect students to learn and the force of habit to evaluate them in the traditional manner with exams and quizzes.”

Practical laboratory classes that correspond to science courses are essential because students perform in a real context and with an established problem. The classes I teach, Matter and the Environment and Matter and Sustainability, include laboratory activities in which students put into practice the theory studied in class, such as: measuring pH, cleaning product generation, gas laws, polymer creation, chemical reactions, renewable energy sources, among others.

To reflect students’ progress in the acquisition of competencies in the laboratory, we use an analytical rubric to define what is expected of them. With the same rubric, the teacher can provide assertive, personalized feedback on the students’ performance. In this way, teachers work together with students to assure the development of autonomy and self-regulation in relation to the disciplinary competencies in the area of science, which include: formulating scientific questions, producing hypotheses, obtaining, recording and systematizing information, applying safety standards, waste management, data collection, comparing results obtained in an experiment, communicating conclusions and documenting information sources.

“The competency-based assessment in the science laboratory encourages students to be aware of their own learning.”

One of the key factors of the competency-based model is the teacher’s feedback to students on their work. Using technology with Blackboard tools, teachers share with students their observations from each laboratory in a personalized manner. In this way, students can take these comments into consideration to improve their performance in subsequent laboratory classes. This reduces the time teachers spend on individual evaluation and facilitates student-teacher communication. The complete study can be seen here.

Another key factor for ensuring the proper implementation of a competency-based model is that student assessment should take place throughout the process. Therefore, as teachers, we need to look for assessment moments across the semester and evidence that reflects student progress. Working as an academy is crucial to enrich and standardize evaluation instruments.

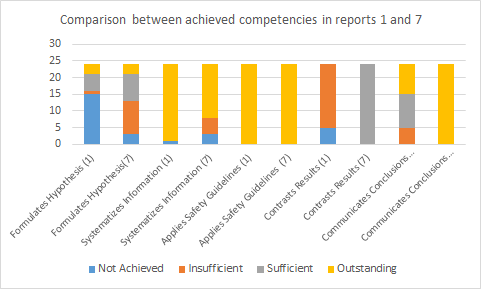

This proposal was implemented during the August-December 2017 semester, with more than 600 third- and fourth-semester high school students. The results (Graph 1) indicate that competency-based assessment improves students’ performance in the laboratory, since it turns them into the drivers of their own learning and makes them more aware of what they are learning.

Graph 1. Comparison of competencies achieved in reports 1 and 7 / Source: Giammatteo (2017).

The rubric was adjusted so that it would also assess student autonomy, focusing more on the use of safety materials and behavior in the laboratory. A mechanism needs to be established in the future to make it possible to demonstrate that the students are in fact checking the teacher’s feedback, since this factor is key to enhancing their performance.

As educators, we should commit to divulging and sharing what we do, so as to improve science education in Mexico and be at the forefront of academic topics. We need to strengthen ties between researchers and educators in order to enrich our work and must be open to the incorporation of new educational practices that could be of enormous benefit to our students’ experience.

About the author

Lucila Giammatteo earned a B.Sc. in Chemical Pharmaceutical Biology from Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. She is a Science teacher at Tecnológico de Monterrey.

This article from Observatory of the Institute for the Future of Education may be shared under the terms of the license CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

)

)

)

Víctor Robledo-Rella, Luis Neri, Andrés González-Nucamendi and Julieta Noguez

Víctor Robledo-Rella, Luis Neri, Andrés González-Nucamendi and Julieta Noguez

Víctor Robledo-Rella, Luis Neri, Andrés González-Nucamendi and Julieta Noguez